(Shalom-SCCRR Department of Research

Director: Prof. W. K. Omoka.

The voice of Peace Practitioners and Researchers)

An Assessment of Inter-Communal Cohesion {© 2020 Shalom-SCCRR}*

By Kennedy Odhiambo, MA.

(Peer-reviewed by Prof. W. K. Omoka, Rev. Dr. Patrick Devine, and Shalom-SCCRR Dept. of Research)

Introduction

While there is a widespread agreement that social cohesion influences economic and social development, and that nurturing a more cohesive society is an important policy goal in itself, little progress has been made in trying to measure it and track progress in this domain over time (Burns, Hull, Lefko-Everett, & Njozela, 2018).

A cohesive society works towards the well-being of all of its members, minimizing all forms of disparities and avoiding marginalization thus decreasing inter-group animosity and insecurities. Moreover, a cohesive society strives to build networks of relationships, trust and identity between different groups; fighting discrimination, exclusion and excessive inequalities; and enabling upward social mobility’ (OECD, 2011).

Years of conflict between the Samburu and Turkana communities are a pointer towards decreased levels of cohesion among these pastoralist neighbors. For instance, insecurity has been a major disruption of the livelihood of the two communities due to rampant attacks and cattle raiding. It is notable that there have been very low levels of inter-communal collaboration both at the institutional level and community level to curb this menace. Furthermore, the rampant attacks have cemented relationships of hatred and animosity among the two ethnic groups thus complicating further the little existing opportunities of jointly addressing their relationship challenges. Years of regional marginalization has been a major destabilizing factor in the efforts among these two communities to secure their economic well-being. Consequently, the runaway poverty, is a major contributing factor to the heightened competition for resources thus a trigger for hatred and non-cooperation among the communities.

The linkage between peace and development is an irrefutable fact. This fact subsumes Shalom-SCCRR’s peace effort (i.e. conflict resolution and reconciliation) and development in Eastern Africa – a vast region with most nations-states characterized by political instability. Moreover, this effort is known to governments of countries outside Africa, some of which are associated with Shalom-SCCRR in a supportive manner. Indeed, in recent times Shalom-SCCRR has organized a three-day seminar on peace building and reconciliation which was attended by Mr. Joe McHugh, Irish Government minister for the Diaspora and Overseas Development, among others. Rev. Dr. Patrick Devine International Chairman and Fr. Oliver Noonan MA, Shalom-SCCRR Country Director were instrumental in the arrangements that resulted in his visit. Subsequently, during a meeting of the European Union’s Ministers for Foreign Affairs and Development in Brussels which addressed humanitarian situation in Africa and elsewhere, Mr. Joe McHugh said the following with particular reference to Eastern Africa and Shalom-SCCRR.

“This was an opportunity for us as a country to give our ongoing commitment to many of the crisis that there are, especially in the Horn of Africa. It was also an opportunity for me to acknowledge the host countries in the Horn of Africa who deal with large numbers of refugees. But on top of that we were focused on our sustainable development goals. We are very focused on – in line with António Guterres (UN Secretary General) as well – at how we can look at and examine the root causes; looking at peace and reconciliation; to looking at how we can bring peace which will obviously lead to sustainable development. We can’t have sustainable development without peace. And I also pointed to the great work that is being done in Northern Kenya by a group called Shalom – interethnic conflict reconciliation – where for the first time in a particular region, even with drought and massive challenges, peace is holding. So we have to look at the solutions. My message today from Ireland to Europe was – if there are examples that are working we should look at them, we should support them,’’ (https://youtu.be/WykmK-hmnDw). Besides, Mr. McHugh in a communication with Shalom-SCCRR, relating to his interaction with its team members at work in the field transforming the conflict between the Samburu and Turkana communities, had this to say about the organization: “I would like to acknowledge the team at Shalom for facilitating the one day interaction which was part of a three day workshop between the Turkana and Samburu communities, and for highlighting the vision which incorporates the spectrum from peace to development and finally to sustained peace. Interestingly, the Shalom team were primarily representative of native Kenyan and a key observation was the extent to which they were familiar with the concept of empowerment and the grass roots/ bottom up model of Community Development. Furthermore, it was evident that the facilitators were competent, articulate and confident in their own abilities which highlighted that Shalom places a strong emphasis on ‘Training the Trainers’ and ensuring proper accreditation is attained before embarking on the important face to face task of conflict prevention and resolution”. (https://shalomconflictcenter.org/the-international-caring-award-brochure-with-updates-from-shalom-sccrr/)

This above paragraph is more than just a mere part of the introduction in that it constitutes the undergirding standpoint of what is discussed in this Samburu-Turkana conflict brief.

The general arguments presented in this descriptive analysis is a product of empirical Research conducted by SCCRR in 2012 on the Turkana-Samburu conflict. Additionally, the paper draws data from the conflict and project monitoring activity that has been continuously undertaken by SCCRR for the past 2 years. Finally, the experience that has been obtained by SCCRR in the course of its implementation of peacebuilding activities among the Turkana and Samburu has provided supportive information. Desktop research additionally has provided sufficient information for this paper.

Contextual background of the conflict:

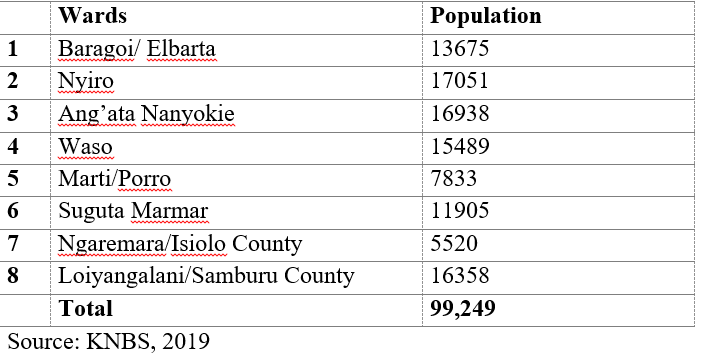

The arid/semi-arid northern Counties (Turkana, Baringo, Marsabit, Samburu, Laikipia) are part of a conflict-affected regions in Kenya (PRAGYA, 2019). The Turkana and Samburu ethnic groups are among the many groups that live in this conflict affected region particularly in Turkana and Samburu counties. The two communities have been embroiled in decades of interethnic conflict particularly in villages where they have been resident neighbors. SCCRR has learnt through its conflict intervention experience that the conflict line between the two communities starts from Ngaremara in the Southern border of Samburu and Isiolo Counties to Loiyangalani at the shores of Lake Turkana in Marsabit County. Particularly the conflict pitting the Turkana and Samburu is mostly experienced in about 8 wards in Samburu and its neighboring counties of Isiolo and Marsabit. These wards are Ang’ata Nanyokie, El-Barta, Baragoi, Nyiro, Suguta Mar Mar and Archers Post in Samburu County, Ngaremara in Isiolo. Additionally, the Samburu-Turkana conflict escalates to the Southern Shores of Lake Turkana into Loiyangalani ward particularly in Sarima, Ghatab, Lonjorin and Arapal villages.

The Population of the communities living in these 8 wards stands at approximately 99,249 as it is indicated in the table below (KNBS, 2019).

Whenever conflicts erupt in the wards mentioned, a number of people are affected in various ways and the collaboration between the ethnic groups is highly compromised. The conflict impacts on the general livelihood of these communities because of the negative impacts on institutions of learning, health facilities, markets, and farming.

The Turkana and the Samburu communities have a livelihood that is widely dependent on pastoralism and crop production. While the Turkana people are predominantly pastoralist, the Samburu people practice both pastoralism and farming almost in equal measure. In addition, both communities are also small scale traders trading mainly in household goods and food items. The livelihood for the two communities can be a reason for lack of cohesion or a cohesive community depending on how the perception of the two communities.

Causes of the conflict and their dynamics:

The lack of cohesion between the Turkana and the Samburu has historically manifested itself in various conflict situations key among them being road banditry, cattle rustling and cattle theft, gender based violence, intra and inter-ethnic attacks. These violent situations have impacted the social fabric of the two communities in various ways. First, cooperation in the attainment of economic progress has been compromised due to the inability of the two communities to share resources and social amenities. For instance, Loiyangalani which is home to about 5000 people of mainly Turkana, Samburu, Rendile and El-molo origins often experience closure of its primary and secondary schools upon an eruption of a conflict incident. Moreover, the main protagonist communities in the conflict in Loiyangalani have for ages faced a challenge of trading with each other in both livestock and food crops whenever there is a rise in tension between them. According to SCCRR’s analysis of the Turkana Samburu conflict, lack of cohesion has been structurally associated with marginalization, conflict memory and negative perception of the ethnic other (SCCRR, 2012), the dynamics in each of the structural causes of conflict have been discussed below.

Marginalization

Marginalization and regional imbalances is seen as one of the crises that various communities of differing ethnic origin, class, generation and gender have persistently experienced (Stiftung, 2012). Stiftung further argues that Kenya has suffered imbalances of resource distribution which have continued to entail a dark lining of inequality based on region, ethnicity, and class. Additionally, poor road infrastructure has continued to marginalize the already marginalized communities as public services continue to exhibit generalized ethnic imbalances in favor of communities whose members are occupying the positions of power. Some marginalization has left communities like Turkana and Samburu with little options but to compete over the scarce resources for their survival thus hindering any possible collaboration between the two communities. In most cases, such competition over scarce resources have taken on ethnic undertones whereby one ethnic community has waged attack on the ethnic other with the aim of neutralizing them and have the resources available for themselves.

According to Stiftung, access to public services is a key factor behind marginalization. He asserts that access to public services such as education and health care and majorly provided by the government. Access to education is particularly important to understanding the perpetration of inequalities since independence. (Stiftung, 2012). One may say that failure of the government to provide Functional institutions in marginalized areas places them at the center in the conflicts relating to marginalization. Culprits in such conflicts are therefore the representatives of government at the community level who either participated in executing wrong government policies or did nothing to challenge such policies that marginalizes the communities. Such actors include the chiefs and local administrators for instance, the ward administrators and even the security agents.

While elders have consistently played the role of being agents of cohesion building at the community level, they have also been instrumental in diminishing the same cohesion through their collaboration with some of the main spoilers’ key among them being the political class. Elders in both communities have always been a trusted institution and as such have midwifed various preventive and transformative conflict management initiatives thus successfully bringing to an end rather volatile situations. However, the influence and the trust that they have from the community have been exploited by spoilers who seek their support in order to drive their selfish agenda which at times is not pro-peace.

Conflict memory

Conflict and memory are often two sides of the same coin, which seamlessly feed into each other. On one hand, conflicts deeply mark the memories of both individuals and collectives, thereby hampering future reconciliation. On the other hand, memory is behind many conflicts, insofar as certain ways of remembering dramatic episodes (whether recent or remote) imply bringing the past into the present and with it the old scars, grievances, resentments, hatreds, and senses of revenge (Wagoner, 2016). Each community memorizes the incidents of violent attacks done to them by their adversaries, so the feelings of hatred were gradually built up and passed over the decades to the next generation. The long standing animosity is not therefore an outcome of recent event, but rather a moral obligation, or a part of cultural identity that current generation must embrace respect and pass to the next one. Such memories certainly do not help processes of reconciliation as both communities feel that some kind of atonement must be done before peace is restored and it is this desire for atonement that breed into violent interethnic attacks targeting one ethnic community or the other. Conflict memory is therefore a factor that has compromised the social cohesion between the Turkana and Samburu communities (Shalom-SCCRR, 2012). This is depicted in the past and present conflict experiences that each of these communities have faced in the hands of the other. The horrific scenes of death, permanent injuries and destruction have constantly brought negative feelings of hatred and deep desire to revenge and this feeling has historically been passed from generation to generation.

Forgiving the past in most cases is easy but forgetting the past is a big challenge. Remembering the past does not usually materialize into violent conflicts by itself. Rather, there are individuals in the communities that give direction to the emotional pains that are associated with the past. The Churches along the conflict line mentioned, have played a fundamental role in teaching their congregations to forgive the past and forgive themselves. However, there are some members of the communities (Turkana & Samburu) who believe that the only way to make peace with the past is revenging the past through what they perceive as justice. Such individuals may be widows and widowers whose relatives might have been victims of the past violence or parents whose kids were brutally murdered in the raid or sisters whose brothers were involved or brothers whose brothers were victims of the past. Sometimes influential leaders of the community like the Chiefs and the elders whose young warriors were killed in the past would spread narratives aimed at avenging the deaths of their community members or politicians who seek electoral positions may use revenge narrative to allow the electorates to elect them to those political positions. Either way giving the conflict memory meaning and need for revenge is a role that is played by individuals in the community at different degrees in which case while the elite youths’ fun the need for revenge through social media the Moran’s execute the revenge attack through attacking the ethnic other for example according to the Shalom-SCCRR conflict monitoring report 2018-2020, while the elders played a fundamental role in de-escalating the violent conflicts and revenge attempts through inter-dialogue between the two communities (Turkana & Samburu), the reports observe that 95% of the attacks were lodged by the Morans (Shalom Conflict Monitoring Report, 2018-2020).

Negative perception: (Us Vs Them Contrast)

While identity by itself is not negative, and in fact is an important aspect for any community, it can be a cause of conflict, especially when it takes a shape of “us” versus “them” dichotomy (Shalom-SCCRR, 2013). “Us” is one’s ethnic group (In-group) whereas “them” are those who are ethnically different from “us” (Outgroup). The in-group are alike in “essential” ways and either in reality or by perception share little or nothing in common with the outgroup. The dichotomization of us versus them; a pervasive thinking across Kenyan communities has yielded high levels of segregation among Turkana and Samburu ethnic groups and strengthened the negative ethnic grouping mentality. Each group constantly sees the other as profoundly different; a difference which provides the in-group with a justification for discriminating against the outgroup especially when it comes to access to political and economic opportunities. The discriminatory practices are often perceived as ethically justifiable so long as the results are beneficial to the in-group regardless of the negative consequences that may befall the outgroup.

Lack of cohesion between the Turkana and Samburu is not just a present phenomenon since the conflict has existed between the two communities thereby shaping their narrative about each other. Common history is an ethnic marker. – i.e., one of the means whereby social and political boundaries between Turkana and the Samburu have been maintained. For instance, the history that defines the Samburu people as a community coupled by the naming of the county as Samburu county has often made the Samburu people to feel that the county is theirs and therefore they have the primary ownership of the county and all its resources. The native Samburu person hence feels that the Turkana only enjoys the right to service provision and resource access in Turkana County and not in Samburu County; a position that constantly triggers outrage and conflict among Turkana people who have historically been residents within Samburu County.

Turkana-Samburu violent conflict expressed in terms of raiding/stealing livestock occurs in specific cultural settings. Culture shapes what each community considers valuable and worth fighting over. The conflict occurs partly because they come from different cultures and with different assumptions. For instance, both these communities exhibit a cultural bias that one should never accord equal value to the ethnic other; a bias which has bred deep ethnic hatred. In deed each of the two communities have nick named each other with the names of wild animals that are often not so friendly to human beings. The Turkana refer to the Samburu as ‘Ngorr’ (enemy) while the Samburu refer to the Turkana as ‘Ngume’ (Black people). This animalization of the ethnic other is meant to dehumanize them and justify brutal and inhuman attacks against them.

Negative perception is a product of history of which women play a primary role in inculcating upon their children. In this case Children grow with the narrative of hate through the narratives shared to them by the parents most particularly their mothers. It is a very common practice among Samburu mothers to stop their young children from crying by telling them, “stop crying I will call for you a Turkana”. The other party responsible for spreading distorted narrative of hate are the politicians, however these days with the rise in technology, there is a widespread sharing of information through the social media by the elite youths, such information is based on the narrative that the elites have received form either the parents or the politicians.

Peacebuilding and conflict mitigation measures:

Organizing, empowering and engaging local community structures

One of Shalom-SCCRR strategy of building social cohesion is capacity building of the local communities with critical, analytical and peacebuilding techniques. Shalom believes that with necessary skills the communities can be the architects of their own future. According to Dandy & Andy, (2013) researching on social cohesion, training among other strategies is key to building social cohesion between rival communities

Shalom-SCCRR’s basis for capacity building among community groups is research. In order to disabuse all rumors and conjectures about the possible causes of the Turkana-Samburu conflict, Shalom-SCCRR engaged in a rigorous empirical study of the underlying causes of this conflict with a view of activating interventions that are responsive to the causes identified. This research coupled by the continuous analysis of the Turkana-Samburu conflict and its dynamics have been quite instrumental to Shalom in the design of its methodology of conflict response along the Samburu-Turkana conflict divide.

The onset of Shalom’s conflict intervention measures is the capacity building of key influential opinion shapers with knowledge, skills and techniques of conflict transformation. This begins with identification, organization and training of key community opinion shapers with skills necessary for building social cohesion. In the past two years alone shalom has successfully established and empowered 10 community groups with an average of 45 key opinion shapers along the conflict line stretching from Isiolo, Samburu to Marsabit in the wards affected by the conflicts. Other than acquiring skills and techniques of peacebuilding, the 450 community leaders have themselves undergone a process of transformation in perceptions, attitudes and conflict motivating behavior. Their readiness to take an active lead role in conducting activities aimed at building greater social cohesion among the Turkana and the Samburu Communities is a guarantee.

Joint community action (Problem solving strategy)

Shalom-SCCRR empowered community groups along Turkana-Samburu conflict line have demonstrated remarkable improvement in their collaboration towards initiating problem solving strategies not just within the in-group but also jointly across the two ethnic groups. In all the 10 conflict locations where Shalom has intervened along the Turkana-Samburu conflict line, the methodology has focused on strengthening of conflict intervention and institutional structures through identification and training of organized groups made of the communities’ most influential local opinion shapers. The methodology has further laid emphasis on strengthening the capacities of selected community resource people who have been actively involved as conflict early warning agents, community conflict mediators and negotiators and support for community driven integrative problem solving. The existing local support for conflict intervention has contributed to a steady reduction in incidences of hostilities among the two ethnic groups and enhanced desire for collaboration and concern towards each other. Conflict monitoring data collected between 2018- 2020 shows a 67% reduction in the number of conflict incidences. SCCRR-Shalom peace groups interventions have played a key role in the reduction.

The result of such interventions have led to restoration of relationship between the two communities in places where they were initially in deep hostile behavior towards each other. Tuum and parkati in Samburu North is one such place. The Turkana from Parkati and the Samburu from Tuum who were once fierce neighbors are now able to share markets, pasture, water points, schools, health facilities among other common facilities.

Peace Education and Development Support

Shalom intervention in schools in Samburu County is unparalleled in the areas of construction of school amenities- like fences, classrooms, dormitories and laboratories and toilets. Additionally, Shalom-SCCRR has focused on the supply of schools with learning materials such as books, desks, laboratory equipment, sanitary towels for the girls. An analysis of SCCRR’s development reports for the past two years reveals that shalom-SCCRR has provided development support to 83 percent of the 21 that were mapped out as schools that depict high levels of vulnerability to conflict across the three counties. Schools development has enhanced cohesion by providing increased space where more children can access formal education and opportunity to undergo transformation into a culture of peace. In addition to that, Shalom – SCCRR established and trained peace clubs in inter-ethnic schools across Isiolo, Samburu and Marsabit so as to enable them to build cohesion in these schools and by extension promote a culture of peace through the promotion of interethnic schooling.

Apart from the school development support intervention approach Shalom-SCCRR has established peace clubs in most of the schools found in conflict areas. These structures within schools have been instrumental in enhancing cohesive environment between the two warrying communities. according to the conflict monitoring report for 2018-2020 Shalom-SCCRR has support 71% of the Schools. Shalom-SCCRR has also heeded to the plea of schools going girls whose learning are mostly interrupted because of lack of sanitary pads. Shalom SCCRR has supported school going girls from the two communities with sanitary pads and will continue to do so. These schools have in turn become spaces for building cohesive communities as even members of the school fraternities have been involved in inter-dialogue process aimed at enhancing a culture of peace.

Conclusion

Shalom-SCCRR has been integral to changing the conflict situation between these two warrying communities so much so that even before the raid is planned and executed, the information will have reached the elders who in collaboration with other stakeholders like the youths, the women and the religious representatives, organize for dialogue aimed at de-escalating the conflict. Tuum Parkati, have had success stories in managing the conflict through sharing information and dialogue aimed at returning stolen livestock to the aggrieved or dialogue over compensation by the known perpetrators. This paper has observed that though the empowered local community leaders dialogue between the two communities have been successful leading to sharing of pastures and water points that were previously a point of contention. The school development support that was a major focus for Shalom-SCCRR has led to many vulnerable schools being identified and supported and this in turn has improved learning environment for school-going children, improved performance and enhanced enrollment. Shalom-SCCRR established peace-clubs in a number of schools in order to promote dialogue in inter-ethnic schools aimed at building inter-ethnic cohesion in schools. The gap the stand clear and that may need consideration, is the vast area that is affected by conflict, that will require Shalom-SCCRR to expand its strategies to reach out to the communities that have been affected yet no practical intervention has been conducted in those areas.

* This document is copyright to Shalom-SCCRR and cannot be reproduced without permission. Quotations from it should be acknowledged to Shalom-SCCRR

References

Eastern Africa: Shalom-SCCRR receives United Nations (UN) Accreditation

Burns, ,. J., Hull, ,. G., Lefko-Everett, K., & Njozela, L. (2018). Defining Cohesion. SALDRU, Working paper no 216.

Dandy, J., & Sala, E. (2013). Research into the Current and Emerging Drivers for Social Cohesion,. Perth: Edith Cowan University.

Ngichabe, G. (2017, April 23). Turkana and Samburu take further steps in Conflict. Retrieved from Shalom-SCCRR: https://shalomconflictcenter.org/the-samburu-and-turkana-take-further-steps-in-conflict-transformation/

OECD. (2011). Perspectives of Global Development 2012: Social Cohesion in a shifting world. Paris: OECD Publishing.

PRAGYA. (2019). Conflict Assessment. PRAGYA.

Samburu County Govt. (2018, February). Samburu County Government. Maralaal: County Government of Samburu. Retrieved from Samburu County Integrated Development Plan.

SCCRR. (2018, Jan 3). Samburu – Isiolo Project Design. Nairobi.

Shalom- SCCRR. (2013). Nairobi: Shalom-SCCRR.

Shalom-SCCRR. (2013). Research Findings on the Turkana-Samburu Conflict. Nairobi: Shalom-SCCRR.

Stiftung, F. E. (2012). Regional Disparities and Marginalization in Kenya. Nairobi: Elite Pre-Press Limited.

UNDP. (2009). Annual report: Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery. New York: UNDP.

Wagoner, B. (2016). Conflict and Memory: The Past in the Present. Peace and Conflict Journal of peace Psychology, Volume 22.

By Kennedy Odhiambo, MA,

Program Officer

Shalom Center for Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation