(Shalom-SCCRR Department of Research

Director: Prof. W. K. Omoka.

The voice of Peace Practitioners and Researchers)

AN ANALYSIS OF THE LAND AND BOUNDARY RELATED DISPUTES IN NAKURU COUNTY {© 2020 Shalom-SCCRR}*

By Joyce Wamae Kamau, MA

(Peer-reviewed by Prof. W. K. Omoka, Rev. Dr. Patrick Devine, and Shalom-SCCRR Dept. of Research)

Introduction

Inter-ethnic conflicts in Africa have caused enormous human suffering and produced some of the most devastating consequences in socio-political growth in the global arena. The menace has been dominant in regions wherein different communities embrace divergent social and political views. Recent studies have suggested that ethnic conflicts result from some combination of greed, opportunity and grievances (Turton, 1993). In Kenya, the severity of such conflicts among different ethnic communities was at its peak in the 1990’s; at the onset of multiparty politics era, which saw the country balkanized along ethnic lines.

In Nakuru County, the inter-ethnic conflicts have caused loss of human life, poor inter-ethnic relations, negative ethnic stereotype, land and boundary disputes, forced human displacements, destruction of property, cattle rustling, slow economic growth and disruption of education. Land and boundary disputes played a pivotal role in influencing most inter-ethnic conflicts in Kenya in the post-colonial periods. Since 1991 inter-ethnic violence has erupted with worrying regularity. The conflict has in most cases been attributed to land-based issues (White, 1990).

Therefore, this analysis addresses the factors that at one and the same time cause inter-ethnic conflict and mistrust between the inhabitants of Nakuru County.

History of land and boundary disputes in Nakuru County

Throughout Kenya’s history, land politics and policy have revolved around debates over whose rights are to be recognized by the state, and have raised the fundamental question of the legitimacy of past land allocations. The question of indigenous versus Kenyan settlers’ land rights forms one dimension of this struggle over the distribution of land. Another dimension has to do with the use of state power to allocate land to the rich, as opposed to the poor.

Nevertheless, dealing with land questions in the Rift Valley—where Nakuru lies, was central to economic and political deals by which the radical nationalist movement was defused and Kenya gained independence from Britain. Between 1962 and 1966, approximately 20 percent of the land in the White Highlands was purchased through state-financed and state-run programs, parcelled up to create settlement schemes, and transferred to Kenyan smallholders (Leys, 1975). High population densities in the former African reserves created land hunger that both the colonial administration and the Kenyatta government understood as a political problem which, if left unaddressed, threatened political stability.

In the 1970s more European-owned farms were acquired by the Kenyan government and then granted, sold, or otherwise transferred to individuals and companies in transactions that were financed by the government. For smallholders in Nakuru, there had been three basic modes of state-mediated access to land: Settlement Schemeswhere the state officials were in direct control of the allocation of plots to individual household heads, who were selected on a case-by-case basis by the official settlement authority; Land Buying Companies (LBCs) purchased or leased farms or estates in the former White Highlands from the government, often from the Settlement Fund Trustees (SFT), and then subdivided these holdings among individual (family) shareholders; and forests lands that became a caisse noire of patronage resources that were used to reward the ruler’s friends and to build political support (Southall 2005:149). In the 1940s and 1950s, for example, when the colonial government decided that there were too many African “squatters” on the white-owned farms part of this surplus population was forcibly resettled in forests.

At the grassroots level, rival groups have often stood on opposite sides of a distributive conflict that has been structured and stoked by the land-allocation policies of Kenya’s governments, both colonial and postcolonial. All of Kenya’s governments have used their discretionary powers over land allocation as an instrument of distributive politics, granting land access strategically to engineer political constituencies that would bolster them against their rivals. For this reason, disputes over access to land in Nakuru and its environs are hugely intertwined with disputes over how state power has been used to gain political advantage, lock in these advantages, and create winners and losers in the national political economy at large.

Key stakeholders and actors in land and boundary disputes in Nakuru

Primary stakeholders: elders, local administration, youth.

Secondary stakeholders: politicians, government officials (public sector).

Tertiary stakeholders: religious leaders, section of the local administration, NGOs, civil societies, elders.

Spoilers: politicians, women/men representatives, elders, youth, political elites.

Categories of land and boundary disputes in Nakuru

The quest for land is insatiable therefore it is important to understand the categories for the land and boundary related disputes—that builds upon the kind of land involved (state, private or common), the specific object of the conflict as well as the legitimacy of actions and the level of violence used by the parties. In Nakuru, these categories are:

- Ownership conflicts due to legal pluralism, lack of land registration; and between state and private/common/collective owners.

- Multiple sales/allocations of land.

- Limited access to land due to discrimination by law, custom or practise.

- Violent land acquisitions and unauthorized sales/renting/leasing of private land and common land leading to clashes.

- Evictions by land owners and illegal evictions by state officials acting without mandate.

- Disputes over the payment for using/buying land and value of land.

- Conflicts due to land/agrarian reforms.

- Conflicting claims in post-conflict situations.

- Land grabbing by high-ranking public officials, illegal sales and illegal leases of state land (including concession land, forests).

- Improper land privatization (e.g. unfair land distribution or titling).

Conflict causes and dynamics

Land and related resources such as water and biodiversity play a vital role in the livelihoods of communities. Given its significance, access to and availability of land-based resources are critical in ensuring real and long lasting improvement in social, economic and political well-being; especially in vulnerable societies that are prone to turmoil and conflict. The question of the use, ownership and access to increasingly scarce land and related resources has been at the centre of protracted conflicts between ethnic communities in Nakuru County. Heavy reliance on land is very high in the county, as the region is arable and highly productive. Different ethnic communities inhabit the county to purchase land, since it’s considerably cheaper than in other areas. In times of conflicts, those who purchased land in the recent past are considered “foreigners” and hence get threatened of eviction or are eventually displaced.

The land and boundary problem in Nakuru is made up of a complex of causes that deepen the level of mistrust among the inter-ethnic communities living there. These causes can be categorized into such broad categories as political, socio -economic, socio-cultural, legal/juridical, technical (land management) and other causes.

Land scarcity

There has been an absolute shortage of land or skewed distribution of land among the inter-ethnic communities in Nakuru, leaving them with little or no land. The land scarcity has been associated with: environmental degradation which take land out of use, decreasing the supply of farmland; concentration of land in the hands of a few, increasing land scarcity and creating a sense of unfairness; and large-scale commercial farming. Land scarcity is not absolute as a cause of land and boundary conflict-but should be treated with caution to avoid generating tensions that can fuel conflict.

Political causes-institutional changes

These are the causes that reflect the changes in the political and economic system including nationalisation or privatisation of land. Since the post-colonial periods in Nakuru, there has been a number of factors that have made it easy for land conflicts to thrive such as lack of political stability and continuity, political corruption that promotes land grabbing; and political (and economic) support for farmers that are well connected and associated with the political elite to the disadvantage of poorer peasants. Similarly, politicians have been using political campaigns to promote divisive ideologies on ownership of most of controversial lands in the area. The effect of this has been a divided society along ethnic line with land or boundary grievance at the core.

Socio-economic causes

Poverty-related marginalisation/exclusion is quite a major cause of land conflict. Poverty by itself is unlikely to lead to conflict – however the ‘poor’ often lack political voice and organisation to defend themselves. Nevertheless, horizontal inequalities and social exclusion, particularly when they coincide with identity increase a society’s predisposition towards violent conflict. Such background conditions end up being exploited by politicians in Nakuru County. Subsequently, the vulnerable communities end up losing as they are not in a position to voice out their land related issues and as a result are excluded from any decision making in regards to grabbed land, illegal sale of land etc.

Extremely unequal distribution of power and resources (land) is also a major cause. When land and other resources on the land gain value, triggers conflict especially if there is an underlying uncertainty over who has legitimate rights to the resource. In Nakuru county, this scenario has been a major cause of corrupt actions and self-dealing by leaders—government officials and traditional leaders—who transfer lands to benefit from the rising value. In other cases, the forests in the area trigger a rush to lay claim to land unless ownership is clearly established and enforced. Similarly, local land conflict has also been triggered in a number of areas where either a government agency or donor project builds an irrigation system or a road to support farmers and access to markets-without proper representation and inclusion of all ethnic communities in the area. In communal land areas, lands are less available due to past transfers by leaders, because of either urban expansion or land to develop infrastructure causing grievances. Past transfers have led to community members losing homes and livelihoods. This has led to subdivision of lands into increasingly small parcels. Grievances associated with past land transfers are another factor that drives some community land conflict.

The local population in Nakuru is rising causing communities to compete and violently engage to control increasingly scarce resources. In Molo and Kuresoi sub-counties, where land governance systems are weak and population pressures are rising, underlying land conflict between family; youth and elders; women and men over access to land, boundaries and inheritance claims is inevitable. Rising population and pressures on land has been pushing some communities to new areas in search of farmland, forests, pastures and water. In other cases, displaced groups have been invited to, or relocated to, the area by a traditional authority or government leader. These movements make land and resources much scarcer and contestable by part of the community that were not consulted/involved during compensation triggering conflict.

Socio-cultural causes

These causes of land and boundary related conflicts depict low level of education and lack of exposure to the information on institutions that handle land issues and mechanisms of land markets in Nakuru County. The level of education among the grassroots communities is still low thus affecting the decision-making process undertaken by the public which is normally underpinned by the consideration of rationality. Additionally, the traditional values and structures among the inter-ethnic communities that should be protecting them have been deteriorating especially when there is corruption in handling land disputes. This escalates the grievances on land and as a result promoting strong mistrust within intra and inter-ethnic communities.

Legal and judicial causes

These causes highlight institutional shortcomings that reflects the absence of official regulations and institutions governing clear and definitive land ownership status in Nakuru County. There are legislative loopholes in the system that reveal contradictory legislation depending on the elite involved. The elites take advantage of ‘the poor/disadvantaged’ grassroots communities that have limited/no access to law enforcement and jurisdiction and the only access they have to formal law is not sufficiently disseminated to them for understanding. The only hope the communities have is in traditional land law that is normally without written records or clearly defined plot and village boundaries that can regulate, protect and provide legal certainty especially when there is sale and purchase of land.

Technical causes

These causes also highlight the institutional shortcomings when land and boundary related conflicts are discussed. There has been a lot of cases that reflect missing or inaccurate surveying that heightens the level of mistrust within the inter-ethnic communities living in Nakuru County. Missing land register (e.g. destroyed) in the land offices that indicate the planning of proper land use and sale have caused ripple effects on the relationship among the communities. Improper transfer of rights to land as a result from the sale and purchase of land has been a major underlying cause of the conflict. This conflict occurs mainly when one party feels there is no equal distribution of the sale of land from the seller who is backed by interested elites hence rankling the affected stakeholders. The effect of this is communal tensions among the grassroots communities leading to prolonged conflict.

SCCRR Peacebuilding and Conflict Mitigation Measures

(See at https://shalomconflictcenter.org/)

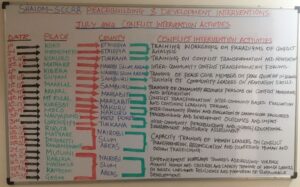

Shalom-SCCRR’s unique and extensive methodology has taken root in understanding the role that land and boundary related disputes play in influencing intercommunal conflicts in Nakuru County particularly in Molo and Kuresoi sub-counties. The quantitative and qualitative analysis done through Shalom-SCCRR’s conflict monitoring system, present detailed evidence that indicates that ethnic mistrust is at the core of intercommunal conflicts and it manifests as land and boundary dispute. It is in this vein that Shalom-SCCRR sort to address mistrust by providing space in the community level for extensive conflict analysis to identify and analyse the underlying causes, dynamics and parties; hold inter-ethnic dialogues, community conversations and joint peace initiatives. There have been several sessions with the key stakeholders that focus on enhancing capacity of the key stakeholders to build structures that promote cohesion and hold these dialogue forums. These trainings impact analytical and technical skills and knowledge in trust building. The trainings also seek to promote genuine relationships among the affected populations and enhance their capacity indirectly in handling land and boundary related disputes.

Most land conflicts are local, as is land itself, those most intimately interested in them are the affected local communities. There are needs within those communities for opportunities to discuss grievances and trigger events in fora insulated from political pressures, but then to participate in dialogue on these issues in ways that politically empower them. Intensive training of the key influential stakeholders (elders, local administration, women and men representatives, youth, religious leaders, teachers, and civil society representatives) is one of the strategies of Shalom-SCCRR to curb this. The various stakeholders are trained on relevant modules of trust-building, understanding the paradigms of conflict, conflict transformation and reconciliation depending on the stage they are in the conflict cycle. The knowledge is impacted and skills acquired in this stage inform the drawing of the action plans. Women participation is highly emphasized as their exclusion from ownership/access to land rights is tied directly to their exclusion from community fora that make key decisions about disputes over land and land ownership.

Shalom-SCCRR exercises considerable care and political sensitivity when engaging with grassroots communities that are affected by land and boundary related disputes. This is because supporting the even legitimate local voices can be easily misunderstood as ‘taking a side’ in the conflict over land. Likewise, Shalom-SCCRR provides structured opportunities for both/all ‘sides’ to express their concerns and positions in a constructive way and have grievances—real or perceived— that endangers the peace of the community addressed. These platforms are dialogues, mediations, community peace circles and community conversations forums.

A major factor limiting the effectiveness of local communities’ participation in discussions of land issues is their poor access to information. They often have a concern, but do not know their rights and are not sure how to articulate their concern or what to ask for. Shalom-SCCRR supports the top leadership structures of interethnic communities with skills and knowledge on facilitation of meetings. The leadership graduate to community facilitators that assist their communities in critically analysing the underlying causes of land and boundary related disputes and develop significant capabilities in settling on a balanced intervention approach.

Similarly, Shalom-SCCRR also contributes to the enhancing the role community socio-economic groups play at the grassroots with an ultimate objective of capacity-building thus giving them a balanced voice. This is important as an in-depth analysis on the land and boundary dispute reflects underlying broader conflicts and a significant disparity in wealth and power between the communities and those with whom they are engaged in disputes, such as elite interests and government agencies. Resolving such disputes in a rationally reduces the chances the conflict becomes increasingly overt and eventually violent.

Conclusion

The complexity of causes leading to land and boundary related conflicts, as well as their diversity and the large number of different actors involved, requires an integrated, system-oriented approach for solving land conflicts and for preventing additional ones. Dealing with land conflicts, therefore, means reconciling conflicting interests over land. It is for this reason that Shalom-SCCRR has continued over the years to support the establishment of a legitimated and widely accepted framework in Nakuru that re-establish mutual respect and trust among the conflict parties.

* This document is copyright to Shalom-SCCRR and cannot be reproduced without permission. Quotations from it should be acknowledged to Shalom-SCCRR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Akiwumi, A.M. Report of the Judicial Commission Appointed to inquire into Tribal Clashes in Kenya, 31st July, 1999.38-55

Frye, Timothy. 2007. “Economic Transformation and Comparative Politics.” In Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics, edited by Carles Boix and Susan Stokes, Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics, edited by Carles Boix and Susan Stokes, 940–68. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harbeson, John. 1973. Nation-Building in Kenya: The Role of Land Reform. Evanston, Ill.: North-western University Press.

1 He adds that their “security of tenure is substantially less than that of the Africans involved in the land-consolidation programs [in Central Province] and even of those who have access to land according to traditional rules of tenure” (Harbeson 1973:284–85).

Leys Colin. 1975. Under-development in Kenya: The Political Economy of Neo-Colonialism. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Onoma, Ato Kwamena. 2010. The Politics of Property Rights Institutions in Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Republic of Kenya. 2002 [1999]. The Commissions of Inquiry Act, Report of the Judicial Commission Appointed to Inquire into Tribal Clashes in Kenya (chaired by Hon. Mr. Justice A. M. Akiwumi) (Akiwumi Report). Nairobi: ROK.

Southall, Roger. 2005. “Ndungu Report Summary.” Review of African Political Economy 103 (March): 142–51.

Turton D. (1993). “We must teach them to be Peaceful”: Mursi views on being human and being Mursi. In: Tvedt T. (ed.) Conflicts in the Horn of Africa; Human and ecological consequences of Warfare, Reprocentalen HSC Uppsala.

White C. (1990). Changing Animal Ownership and Access to Land among the Wodaabe (Fulani) of Central Niger. In: Baxter P.T.W. and Hogg R. (edds) property, poverty and people: Changing Rights in property and problems of pastoral Development, University of Manchester, Department of Social Anthropology and International Development Centre, Manchester.

Shalom-SCCRR Workshop reports, Molo and Kuresoi (2013-2020) Unpublished manuscript. Available at Shalom-SCCRR offices.

SCCRR’s participatory peacebuilding strategy in Nakuru County. https://shalomconflictcenter.org/sccrrs-participatory-peacebuilding-strategy-in-nakuru-county/

Conducting an evaluation of activities in Nakuru County. https://shalomconflictcenter.org/conducting-an-evaluation-of-activities-in-nakuru-county/

Empowering Nakuru Communities to Achieve Peaceful Coexistence. https://shalomconflictcenter.org/empowering-nakuru-communities-to-achieve-peaceful-coexistence/

Enhancing Peace through Education and Development in Nakuru. https://shalomconflictcenter.org/enhancing-peace-through-education-and-development-in-nakuru/

Shalom interventions and results; Transforming and healing wounds of ethnic conflict in Molo and Kuresoi, Kenya. https://shalomconflictcenter.org/shalom-interventions-and-results-transforming-and-healing-wounds-of-ethnic-conflict-in-molo-and-kuresoi-kenya/

Preparing Naivasha Surrounding Population for Peaceful Elections. https://shalomconflictcenter.org/preparing-naivasha-surrounding-population-for-peaceful-elections/

Preparing the People of Njoro for Peaceful Election. https://shalomconflictcenter.org/preparing-the-people-of-njoro-for-peaceful-election/

RELEVANT LINKS

By: Joyce Wamae Kamau, MA,

Program Manager (Peacebuilding & Development, Urban Settlements Program).

Shalom Center for Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation