DIMINISHING ROLE OF TRADITIONAL MECHANISMS IN THE MANAGEMENT OF PASTORALIST CONFLICT

(Shalom-SCCRR Department of Research

Director: Prof. W. K. Omoka.

The voice of Peace Practitioners and Researchers)

{© 2020 Shalom-SCCRR}*

By Austin Ngacha Macharia MA,

(Peer-reviewed by Prof. W. K. Omoka, Rev. Dr. Patrick Devine, and Shalom-SCCRR Dept. of Research)

Introduction

In pastoralist communities, intra and inter-communal relations are governed by traditional policies and authorities, which also play a very critical role in conflict management and maintenance of peace. Although traditional mechanisms remain widely respected and trusted in pastoralist communities, the ability of traditional authorities in the form of elders to perform crucial regulation and policy enforcement, particularly in regard to the management of conflicts, has been slowly eroded and in many cases rendered ineffective (Scott-Ville et al. 2011). This paper, therefore, examines the diminishing role of the traditional elders in the management of inter-ethnic conflict between the Turkana and Dassenach pastoralist communities along the Kenya – Ethiopia borderline. The paper has four main sections, viz, contextual background of the conflict; parties and their roles in the conflict; factors affecting the role of traditional elders in the management of conflict; and, Shalom-SCCRR’s strategies to highlight the importance of traditional systems in the management of conflict between the two communities.

The sources of data for this paper were from Shalom-SCCRR’s empirical research conducted along Kenya Ethiopia borderline (2019), continuous field conflict situational analysis reports, workshop reports, and review of relevant empirical research literature on the topic.

Contextual background of the conflict

Kenya Ethiopia borderline has been a battlefield for the Turkana and Dassenach pastoralist communities residing along this borderline. The borderline stretches to Ilemi Triangle; a disputed region between Kenya, South Sudan, and Ethiopia, located in the extreme North of Turkana County (Winter, 2019), and measures between 10,320 and 14,000 square according to Collins (2004). The Turkana and Dassanech communities have had a long history of both conflict and cooperation in which livestock raiding went hand in hand with the preferred socio-cultural and economic lifestyle of pastoralism.

The two communities have been locked in regular conflict majorly over water, pasture, livestock, and recently fishing grounds in Lake Turkana. In the seminal rigorous empirical research on the causes and consequences of the conflict between Turkana and Dassenach, Devine (2009, peer-reviewed by Prof. W.K. Omoka and Prof. R. Mudida) found that the four major underlying causes explaining the Turkana-Dassenach conflict were; competition for environmental resources (water and pasture land); contested territory in regards to boundaries; cultural variations between the Turkana and Dassenach communities, and state neglect evident in the lack of institutions to enable the people to meet their basic human needs and actualize their potentials. The research also found out that the proliferation of small arms was a major subsidiary cause relating to issues indicative of state neglect. These underlying causes and subsidiary factors have not been significantly transformed and continue to persist in the Turkana-Dassenach conflict environment. The findings of Devine’s research have immense relevance and urgency for conflict management interventions going forward.

The persistent inter-communal conflict between the two communities continues to be characterized by manifest violence in a marginalized environment, bringing immense suffering to these communities. Not only has the conflict resulted in deaths, massive loss of livestock, injured inter-communal relationships, disrupted their socio-economic development and livelihoods, but also have limited the mobility of people and their livestock that is crucial to their pastoral lifestyle. The main areas categorized as conflict hotspots along this borderline include Todonyang’, Kokuro, Meyan and Liwan from the Kenyan side, and, Koro, Emomeri, Sies, Damich and Sirimiriet from the Ethiopian side. The total population affected by this conflict is approximately 70,000 people along the Kenya – Ethiopia borderline.

Parties and their roles in the conflict

Different stakeholders are playing different roles in the Turkana Dassanech conflict along the Kenya Ethiopia borderline. As shown in Chart 1 below, 100% of the respondents categorized warriors (morans/youth) as the primary stakeholders (perpetrators) in this conflict. The main reason given was that the majority of the youth are always in the frontline in terms of executing livestock theft, raids, revenge attacks and killings along the Kenya – Ethiopia borderline. 73% and 67% of the respondents categorized political leaders and women as spoilers respectively. According to the respondents, some local politicians occasionally facilitate the warriors (morans/youth) in carrying out livestock theft, raids and attacks. The women according to the respondents contribute to conditions that exacerbate conflicts due to the fact that they benefit from the raided livestock. As a result, they encourage and praise warriors to go for raids while disdaining those who fail to. On the other hand, the religious institutions (Churches), Non-Governmental organizations (NGOs), security agents (Police & Special Forces), local administrators and traditional elders were categorized by all the respondents as peace agents. The respondents noted that there is a changing trend in the recent past whereby the elders are now becoming peace agents as opposed to ‘blessing’ the youth to go for raids.

Chart 1: Categories of stakeholders and their roles in the management of Turkana – Dassanech conflict along Kenya – Ethiopia borderline

Factors affecting the role of traditional elders in the management of conflict between the Turkana and Dassanech communities.

The traditional elders from both the Turkana and Dassanech communities are rarely fronting or even jointly collaborating in conflict intervention as in the past. This has, therefore, rendered the traditional mechanisms for managing inter-communal conflicts between the two communities ineffective.

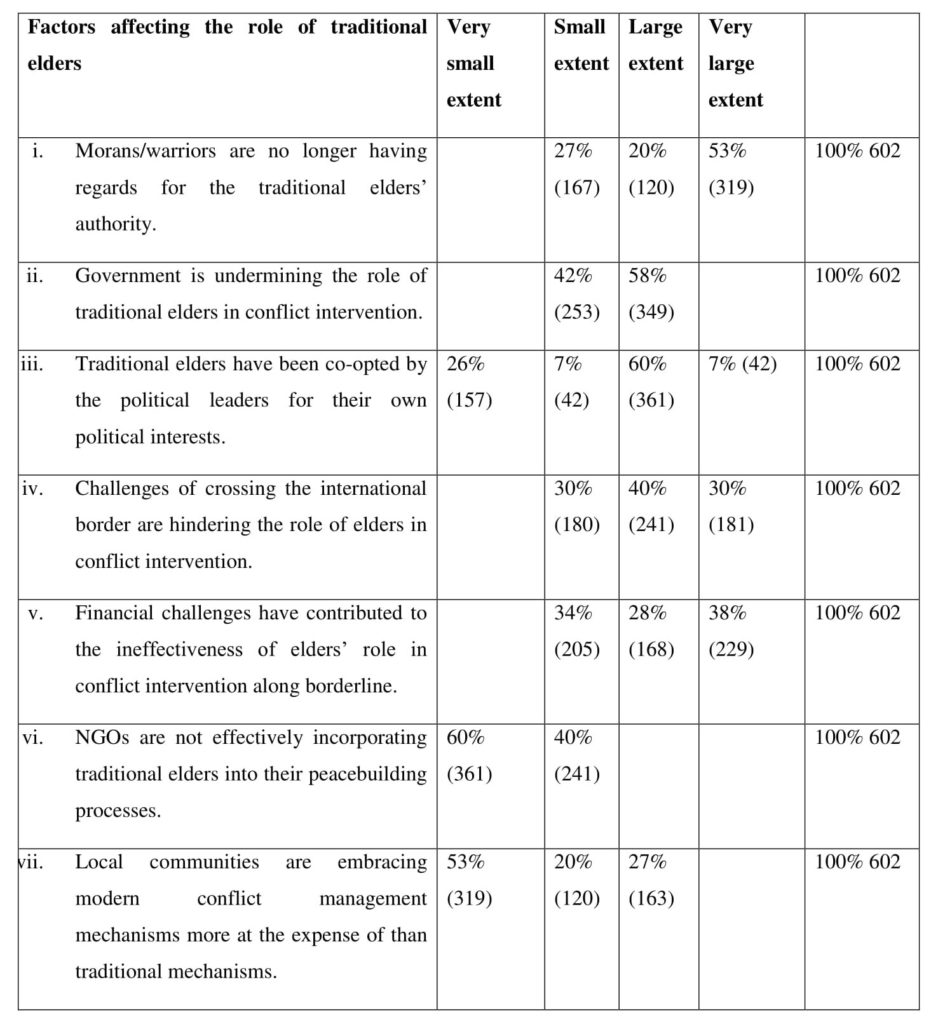

There are a number of factors that are contributing to the diminishing role of traditional elders in the management of inter-ethnic conflicts between the two communities along the borderline as explained in the table below.

Table 1: The extent to which different factors are affecting the role of traditional elders in the management of conflict between the Turkana and Dassanech communities.

Disrespect from the Morans/warriors: 73% (439) of the respondents said that the youth (warriors/morans) are no longer respecting the elders and the traditional hierarchy of authority as in the past. The youth are now able to plan, execute raids and attacks any time without the ‘blessings’ and permission from the elders. In the past, the motives of raiding were geared to community survival and reproduction. At present, however, there is reduction in raids and increased in rampant livestock theft executed by a few youth mainly geared to individual accumulation of wealth. This has, therefore, undermined the traditional motives of raiding, the raiding process and cordial relationship that were previously regulated by the elders. This has led to profound disregard for alliance and cooperation between the two communities that has further created an atmosphere of animosity and vindictiveness. It is also important to note that there is a noticeable shift from livestock raiding to livestock theft.

Government undermining the role of elders: In the past, the elders played an important role in defusing conflict within and between the pastoralist communities. They were able to and counterbalance the aggressiveness and military orientation of the youth (warriors/morans). The elders spearheaded inter-communal dialogues and reconciliation between the two pastoralist communities. According to 58% (349) of the respondents, however, the two government institutions have systematically ignored, overridden and weakened traditional pastoralist governance systems resulting to erosion of elders’ authority and ability to enforce rules and manage conflicts. Governments’ officials have at times overruled customary institutions and authority of elders and made unilateral decisions in pastoralist affairs (including conflict management and peacebuilding) rather than jointly working with elders or in line with elders’ decisions, hence failure to effectively addressing inter-communal conflict in the borderline.

Co-option by political leaders: According to 67% of the respondents, political players have co-opted a good number of traditional elders for their own political interests hence diluting their traditional authority that was preciously vested in them by their communities. The elders are no longer commanding respect from their communities since they have become ‘political vehicles for hire.’ The elders are now acting for the interests of the politicians rather than the interests of their communities.

Challenges of crossing the international border: In the past the elders used to freely crisscross the borderline in order to hold inter-communal dialogues during the periods of conflict and peace. The elders enjoyed some privileges as emissary of peace in these two communities and they were never harmed in their peace mission. However, 70% (422) of the respondents said that the elders are currently finding it very insecure to just cross the international border to either side due to the fear of being attacked by the members of the ethnic other. This is informed by the fact that the two communities have been engaged in protracted bloody conflict over the past years which has severely affected their interactions. Moreover, the restrictions of crossing the international border have also been cited as a challenge hindering elders’ communication and interaction between the two communities. The locals feel that elders cannot effectively spearhead conflict intervention and support peacebuilding processes if they cannot be allowed to move freely along the borderline.

Financial challenges: 66% (387) of the respondents noted that lack of funds for facilitating the elders’ movement and peace meetings have also restricted and hindered collaboration between the elders in conflict intervention. In the past, the elders could walk from one area to another in order to hold peace dialogues. In these meetings, the hosting community used to slaughter a bull and some goats for the elders to ‘consume’ while discussing the affairs of their communities. With the current modernization, it is becoming important for elders to use the current available easiest and fastest means of transport in the form of vehicles and motorcycles. Most elders from these pastoralist communities are not able to raise money for transport hence, they need support from the governments and well-wishers to facilitate their movement which most of the time is not forthcoming.

Peacebuilding and conflict mitigation measures:

Shalom-SCCRR is utilizing three main strategies in supporting the strengthening and revitalization of the local-based traditional conflict management mechanisms and the role of traditional elders in the management of inter-communal conflicts along the Kenya Ethiopia borderline as discussed herein.

Establishment, empowerment and engagement of Traditional Elders’, Youth (Warriors/Morans) and Women Forums along the borderline.

Shalom-SCCRR has established 12 local-based community peace groups along the Kenya Ethiopia borderline. These groups are in the form of Traditional Elders’ Peace Forums, Youth (Warriors/Morans) Peace Forums and Women Peace Forums. The identification and selection of the three categories of stakeholders were done through a rigorous and participatory community process. The justification for the involvement of the traditional elders is to revamp their weakened role in the management of inter-communal conflict in this borderline. The involvement of the youth (warriors/morans) and women on the other hand is based on the fact that the two are most of the time categorized as perpetrators (frontline conflict actors) and spoilers (inciters of the youth to go to raids) respectively. More importantly, in order to enhance effective management of inter-communal conflict between the two communities, there is, therefore, need for the three categories of stakeholders to work together.

Shalom-SCCRR team, whose staff are all qualified with an MA degree in peacebuilding, is spearheading these forums through series of peace trainings with particular emphasis on the analytical techniques and skills for conflict analysis, conflict transformation mechanism, peacebuilding techniques, inter-communal dialogue and non-violent strategies for effective management of inter-communal conflicts. The three forums are trained so as to continuously be at the forefront in; conflict situational analysis, enhance inter-communal communication and sharing of conflict early warning signs, identification and implementation of quick impact interventions, fostering intra and inter-communal dialogues and engaging other local-based community groups through awareness creation forums, and, development and implementation of joint inter-communal peace agreements.

Establishment of a network of Middle level stakeholders along the borderline.

Shalom-SCCRR has established a network of middle level stakeholders constituting of key influential and resourceful government and community leaders drawn from local administration (chiefs, ward & woreda administrators), security agents (Police & Woreda security), and, representatives from local-based NGOs and FBOs along the borderline. The key roles of these stakeholders include conflict monitoring, analysis and reporting; holding community sensitization forums to encourage their communities to frequently utilize the traditional elders in the management of inter-communal conflicts; spearhead community mobilization for conflict intervention through the local-based conflict management structures along the borderline.

Collaboration with local governments and NGOs along the borderline.

Shalom-SCCRR is collaborating with government institutions especially Turkana County (on the Kenyan side) and Dassenach Woreda (on the Ethiopian side), as well as local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like SAPCONE (from Kenya) and Peace & Development Center (from Ethiopia). Shalom-SCCRR has engaged with these institutions in order to support the traditional elders’, youth (warriors/morans), and women forums in conflict intervention through the facilitation of their movement, offering training on peaceful conflict resolution mechanisms and enhancing interaction across the border. Moreover, Shalom-SCCRR has also lobbied these institutions to always involve the Shalom-SCCRR-trained members of these three forums (Elders, Warriors, and Women) in their peacebuilding and development processes along the Kenya-Ethiopia borderline. Shalom-SCCRR and its partners going forward jointly organize and facilitate traditional peace forums to empower communities to nonviolently negotiate the rights and usage of grazing fields-water points-fishing grounds, critique negative cultural variations, abet in strengthening state institutions regarding the provision of basic human needs, clarifying territorial boundaries and eradicating the proliferation of small arms, etc. The importance of rigorous research and the support and utilization of traditional elders and other local-based structures in the management of inter-communal conflicts are critical to the success of these processes.

Conclusion

The traditional mechanisms for conflict management stressed the need of fostering a spirit of peace, mutual respect, value of human life, and cooperation within and between pastoralist communities – in times of peace and in times of conflict. This was effectively ensured through the institution of traditional elders. However, in the recent past, the authority of traditional elders has dwindled majorly because of the factors explained in this paper. Shalom-SCCRR is committed to the continuous strengthening of the local-based conflict management mechanisms through the establishment of a harmonious working relationship between the elders (regulators of the conflict), the youth (executers of the conflict), and the women (the victims & inciters of the youth) in conflict intervention while restoring ‘the lost glory’ in regards to the role of traditional elders in the management of inter-communal conflicts between the Turkana and Dassanech communities along the Kenya – Ethiopia borderline.

* This document is copyright to Shalom-SCCRR and cannot be reproduced without permission. Quotations from it should be acknowledged to Shalom-SCCRR

REFERENCES

Devine, P. (2009). Turkana – Dassanech conflict: Causes and Consequences. (Unpublished master’s dissertation). Hekima Institute of Peace Studies and International Relations (HIPSIR), Catholic University of Eastern Africa, Nairobi, Kenya.

https://shalomconflictcenter.org/turkana-dassenach-conflict-causes-and-consequences/

https://shalomconflictcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Copy-of-SCCRR-Newsletter-Report.pdf

Wimter, P. (2019, 06, 13). A Border Too Far: The Ilemi Triangle Yesterday and Today, by Philip Winter. [Presentation]. Sir William Luce Fellowship papers, Durhan University, Middle East.

Collins, R. (2004). The Ilemi Triangle. Annales D’ethiopie. 20. 5-12. 10.3406/ethio.2004.1065.

Lutta, S. (2020). Turkana’s Todonyang Village deserted as Ethiopia’s Merille militia takes over. Retrieved September 22, 2020, from https://nation.africa/kenya/counties/turkana/turkana-s-todonyang-village-deserted-as-ethiopia-s-merille-militia-takes-over-1186476.

Shalom-SCCRR (2019). Changing Conflict Dynamics among Pastoralist Communities along Kenya – Ethiopia borderline: A critical Analysis. Unpublished manuscript.

Scott-Ville P., et al. (2011). The long conversation: Customary Approaches to peace management in Southern Ethiopia and Northern Kenya. Working Paper 022, Future Agricultures Consortium. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies.