(Shalom-SCCRR Department of Research

Director: Prof. W. K. Omoka.

The voice of Peace Practitioners and Researchers)

IMPACT OF PERSISTENT ATTACKS ON INTER-COMMUNAL RELATIONS IN PASTORALIST COMMUNITIES IN KENYA: AN ANALYSIS OF SAMBURU-GABRA CONFLICT. {© 2020 Shalom-SCCRR}*

By Asha Said Awed, MA.

(Peer-reviewed by Prof. W. K. Omoka, Rev. Dr. Patrick Devine, and Shalom-SCCRR Dept. of Research)

Introduction

Pastoralist communities in Marsabit County in northern part of Kenya have continuously engaged in inter-communal conflicts over the years (Shalom-SCCRR, 2019). These conflicts have resulted to killings, loss of hundreds of livestock, insecurity, destruction of education and health facilities, and disruption of livelihoods among many other negative effects. This paper, therefore, focuses on analysing the impact of the persistent attacks on inter-communal relations in the context of Samburu–Gabra conflict in Arapal and Gas areas of Marsabit County. The paper presents the contextual background of the conflict, parties and their particular roles in the conflict, causes of this conflict and their dynamics, and, intervention strategies being implemented by Shalom-SCCRR to address the conflict.

The data utilised in this paper was generated through questionnaires administered to a sample of 80 respondents drawn from Arapal and Gas areas, monthly field monitoring reports (conflict incidence & project monitoring reports), conflict situational analysis reports, workshop reports and other relevant research literature on pastoralist conflicts in Northern Kenya.

Contextual Background of the Conflict

Marsabit County is categorized as arid and semi-arid lands and it experiences semi-arid climatic conditions with minimal rainfall and extreme temperatures. It is the second largest county in the country in terms of landmass after Turkana County, and it covers an estimated total area of 70,961.2 km2 (Marsabit County CIDP, 2018-2022). The county shares an international border with Ethiopia to the north, and nationally it borders Lake Turkana to the West, Samburu County to the South and Wajir and Isiolo Counties to the East. The County is inhabited majorly by the pastoralist communities namely Gabra, Rendile, Borana, Samburu, Turkana, Burji, Dasannech, Wata and Somali communities (Saferworld, 2015).

Marsabit County has been experiencing a wave of violent conflicts in the recent years especially after the emergence of county governance in Kenya. The patterns of conflicts in the County are complex with different pastoralist communities locked in protracted inter-communal conflicts (SRIC, 2014). The dynamics of inter-communal conflicts particularly between the Samburu and Gabbra communities are predominantly informed by a combination of political, social, economic, cultural and environmental factors. Just like in other pastoralist communities across Northern Kenya, it is important to note that structural dimensions of the conflict pose a very big challenge to the realization of the potentials and aspirations of these two communities.

The conflict between the two communities is geographically located in the areas of Arapal, Gas and Mt. Kulal (Gatab). These are the three main areas where the two communities are living closely to each other in the entire Marsabit County. The approximate population of the people affected by the conflict in these areas stands at 7,000.

Parties and their roles in the conflict

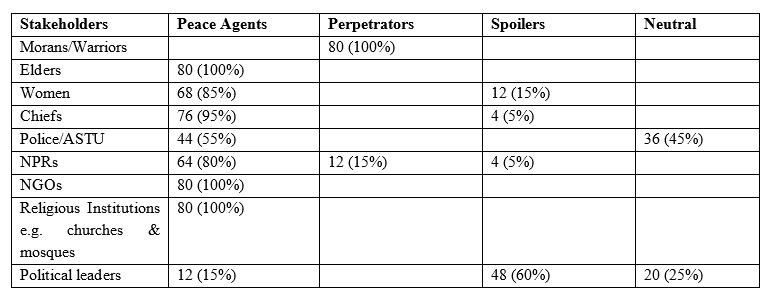

Table 1: Categories of stakeholders and their role in inter-communal conflict between the Samburu and Gabra communities in Arapal and Gas areas.

Different stakeholders are contributing to the conflict between the Samburu and Gabra pastoralist communities as depicted in Table 1 above. 100% of the respondents categorized the youth (warriors/morans) of playing the perpetrators role in this conflict. This resonates with the fact that the warriors/morans are always the ones who execute livestock raids and attacks in pastoralist communities. However, it is important to note that the youth are now conducting these attacks on their own – without consulting the elders – and for their personal benefit and not necessarily for communal interests.

According to the respondents, the elders, the women, the chiefs, the National Police Reservists (NPRs), NGOs and religious institutions are all peace agents. Most of the respondents (60%) on the other hand categorized political leaders as peace spoilers. The main reason for this categorization was because some politicians occasionally incite or even facilitate execution of inter-communal attacks for their own selfish interests.

Causes of the Conflict and their Dynamics

Like in other pastoralist communities in northern Kenya, there are a number of intertwined factors that contribute to inter-communal conflicts between the Samburu and Gabra communities including competition over pasture and water for their livestock, retrogressive cultures, inadequate institutions that provide human security and government services, availability and possession of illicit firearms by the locals, weakened role of traditional elders in conflict intervention, and, political incitements (Saferworld, 2015; SRIC, 2014). All these factors, in one way or another, result to inter-communal attacks. The focus of analysis in this paper, however, is particularly on the dynamics of livestock raiding and inter-communal killings in the context of the two communities.

a.) Livestock raiding

Just like in other pastoralist communities, livestock raiding between the Samburu and Gabra communities has over the years been driven majorly by cultural practices of accumulation of wealth (livestock) for prestige and community survival; commercialization of livestock raiding; and, availability of illegal firearms in the hands of the locals.

Raids among the pastoralist communities like the Samburu and Gabra were meant to traditionally maximize herd sizes in order to ensure communal survival and status. Raids by then were, therefore, a form of response to disasters emanating particularly from livestock diseases and famines (droughts) – replenishing strategy. However, in the later decades of the 20th century, the motivation for livestock raiding shifted to that of self-acquisition. Raids motivated by such tendencies did not occur as a response to ecological or natural calamities but occurred at any time with the aim of acquiring livestock for commercial purposes and individual gain. While the first category of raids hinged on communal interests and was monitored by both communities through social norms, the latter was based entirely on private interests and was controlled by conflict entrepreneurs in the form of illegal arms traders and livestock warlords.

Recently though, there has been a shift from ‘mass raids’ (highly organised with several hundred raiders assembled from all over the community to attack a whole community in a neighbouring locality) and ‘medium raids’ (where several dozens of up to a few hundred raiders from near-by villages come together to raid one village or kraal of a rivaling community)to ‘small raids or theft’ (where a handful of rarely more than 15 raiders).This shift is not only between the Samburu and Gabra communities but also among the pastoralist communities across the northern part of Kenya. The shift is mostly due to the improved communication infrastructure (particularly mobile network and availability of phones) in the area that has made medium and mass raids easy to be spotted and harnessed by government authorities. Small raids on the other hand require shorter organization period and they attract less attention. Moreover, the livestock involved in ‘small raids’ are also a few and easy to drive to the target destinations. It is important to note that availability of illegal firearms among the members of the Samburu and Gabra communities has also intensified the frequency and execution of ‘small raids’ in Arapal and Gas areas.

b.) Inter-communal killings

Inter-communal killings between the Samburu and Gabra communities has claimed many lives over the years. These killings have been promoted by some diminishing retrogressive culture of ‘moranism’; inter-communal revenge; and, inter-ethnic hatred and animosity.

The two communities both practice the culture of ‘moranism’ where the youth (warriors/morans) are initiated or elevated from childhood to adulthood. After this cultural rites of passage, the warriors/morans feel ‘obligated’ to ‘confirm their manhood and stamp their authority’ by conducting some raids that are accompanied by killing of the members from ethnic other. This act has most of the time resulted in retaliation by the aggrieved community: contributing further to an extremely dangerous cycle of inter-communal revenge killings and ethnic hatred and animosity. Moreover, the delay in addressing these killings most of the time aggravates inter-communal revenge attacks targeting innocent members of the two communities (women, children and elderly). The frequency and magnitude of the cases of inter-communal killings is most of the time determined by the state and nature of inter-communal relations between the two communities at a given time.

Impact of persistent inter-communal conflict on inter-communal relations in Arapal and Gas areas.

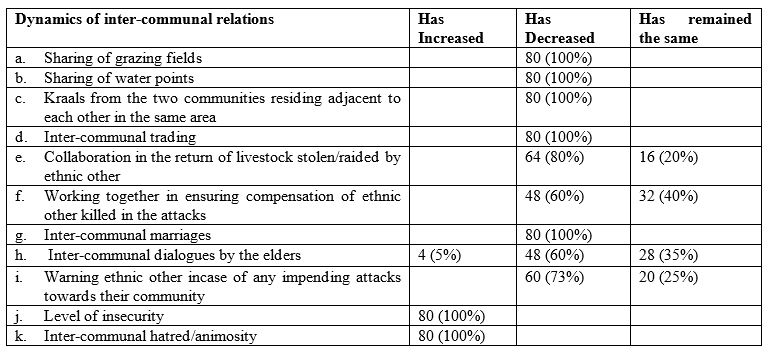

Table 2: Dynamics of inter-communal relations between the Samburu and Gabra communities in Arapal and Gas areas.

From Table 2 above, it is clear that the persistent inter-communal attacks have impacted negatively on inter-communal relations between the Samburu and Gabra pastoralist communities in Arapal and Gas areas. Through conflict situational analysis conducted with the Shalom’s community peace groups in the two places, inter-communal relations between the two communities was said to be bad (Shalom-SCCRR’s conflict situational analysis reports 2018-2020). This state of inter-communal relations was attributed to the continuous attacks manifested in the form of livestock raids and killings between the members of the two communities.

According to the respondents as shown in Table 2 above, sharing of grazing fields and water points between members of the two communities has tremendously decreased over the years. The respondents said that the two communities are currently not grazing their livestock together nor sharing the same water points as before. In order to avoid confrontation, each community now takes its livestock to different grazing zones and water points near their own kraals and villages. The respondents said that residents of the different kraals of the two communities that used to live adjacent to each other have migrated far away from each other due to the fear of being attacked. Moreover, the two communities used to trade livestock with each and even inter-married. However, due to injured inter-communal relations as a result of continuous attacks and counter-attacks, the members of the two communities are minimally interacting with each other.

The respondents stated that when livestock are raided/stolen or people are killed from either side, the two communities rarely collaborate in ensuring the return of the raided/stolen livestock or compensation of the persons killed. According to the respondents, the security agents (police/Anti Stock Theft Unit) and local administrators (chiefs) are the ones that sometimes intervene to spearhead the recovery and return of the raided/stolen livestock. 100% of the respondents noted that there was increased level of insecurity due to the availability of illegal firearms making the members of the two communities to always live in fear. Respondents argued that inter-communal hatred and animosity has increased between the two communities and this was attributed to tenacious inter-communal attacks and unresolved conflicts (wrong-doings) – livestock not returned and persons killed not compensated. This has resulted also to the reduction in the number of inter-communal dialogue meetings conducted by the elders and minimal collaboration in conflict early warning and early response between the two communities.

Peacebuilding and Conflict Mitigation Measures

To contribute to addressing persistent inter-communal attacks between Samburu and Gabra communities, Shalom-SCCRR is working towards enhancement of a well-coordinated local-based conflict early warning and early response (CEW&ER) network, and, fostering of inter-communal dialogue between the two communities.

a. Local-based conflict early warning and early response network

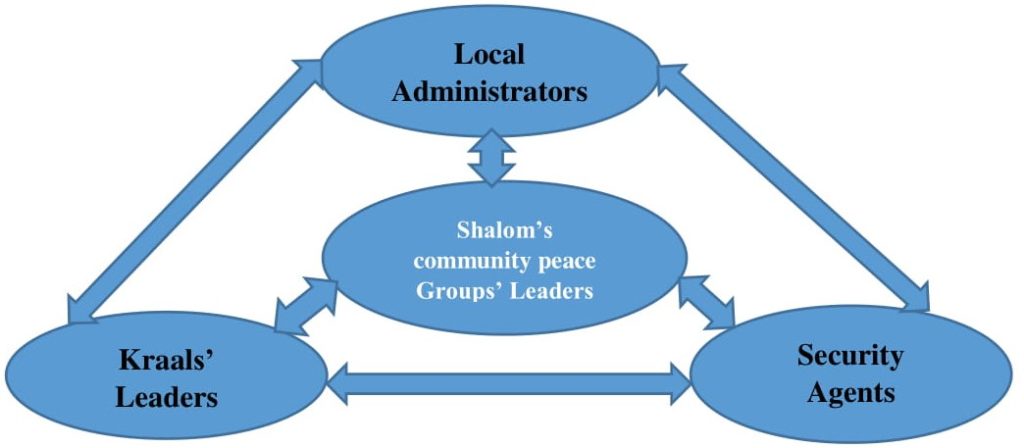

Shalom-SCCRR has established a local-based CEW&ER network as shown in Figure 1 above in order to enhance collaboration and coordination between the two communities in the management of inter-communal attacks manifested in the form of livestock raids and killings. The organization has established and empowered community peace groups both in Arapal and Gas areas whose main role is to be the agents of peace and conflict interventions between the Samburu and Gabra communities.

Through the context of this network (Figure 1),the Shalom’s community peace Group Leaders organize and facilitate monthly conflict situational analysis meetings that are attended by local administrators (chiefs & village elders), security agents (police/ASTU & NPRs) and kraals’ leaders. The main objective of these meetings is to jointly deliberate and establish the state of the conflict situation and propose quick impact interventions to be implemented in order to avert an impending conflict or manage the already existing one.

After the meetings, Shalom’s community peace Group Leaders prepare comprehensive conflict situational analysis reports and share them with all the members of the network. Each of the categories of stakeholders will again share the same reports with their constituents for any further action. From these reports, the chiefs go ahead and prepare security briefs that they share with their superiors (Assistant County Commissioners). The chiefs together with their village elders also hold barazas with the members of their communities in order to create awareness in regards to the conflict and security situation in their areas. The security agents on the other hand prepare their own security briefs from these reports and share them with Officers Commanding (police) Stations (OCS). The Kraals’ Leaders also organize for forums targeting the youth (morans/warriors) and women in order to informally share these reports within their respective kraals.

Whenever there are some tensions or looming attacks between the two communities, the CEW&ER team organize and hold forums with the members of the communities in order to avert the conflicts. However, when the attacks for example have happen and the livestock have already been taken by either community, the team work together in ensuring the recovery and return of livestock back to the rightful owners. In September 2020, for example, the team coordinated and facilitated the recovery and the return of 109 livestock (camels and cows) to the members of the Gabra community after they had been raided by the youth (morans/warriors) from the Samburu community. In September 2019, the youth from Gabbra community attacked a Samburu kraal and drove away almost 30 livestock. The CEW&ER team in collaboration with the government officials intervened and coordinated the immediate return of the raided livestock to the members of the Samburu community.

b. Local-based Inter-communal Dialogue Framework

Shalom-SCCRR is currently in the process of establishing a local-based framework for fostering inter-communal dialogues between Samburu and Gabra communities in Arapal and Gas areas. The Joint Inter-communal Dialogue Committee will be constituted and the representatives will be drawn from both communities. The committee will develop the Joint Social Contracts for Peace (SCP)/Intercommunal Peace Agreements (IPAs) through a series of dialogue meetings facilitated by Shalom-SCCRR. The committee will also spearhead the management of inter-communal conflicts through continuous inter-communal dialogues in regards to the sharing of grazing fields and water points, collaboration in the return of livestock raided/stolen and compensation of the persons killed. This will go further in enhancing inter-communal relations that will results to the reduction in cases of inter-communal attacks between the two communities.

In the meantime, some members of the CEW&ER team (the chiefs, elders and kraal leaders) are currently the ones organizing and facilitating some minimal local-based community dialogues in Arapal and Gas areas.

Conclusion

The persistent inter-communal attacks between Samburu and Gabra communities have enormously impacted on their inter-communal relations. The continuous inter-communal attacks have injured their relations to the extent to which there is minimal interaction between the members of the two communities. The dynamics of this injured relations is majorly manifested through the decreased inter-communal dialogues, lack of collaboration in the return of livestock stolen/raided, lack of compensation of the persons killed in inter-communal attacks and reduction in inter-communal trading.

Shalom-SCCRR is currently working with the members of the two communities in the long term process of rebuilding their relations and cultivating peaceful futures. The organization is, therefore, committed in the strengthening of the local-based structures – CEW&ER and inter-communal dialogue framework – that will be utilised in the effective management of inter-communal attacks in Arapal and Gas areas.

* This document is copyright to Shalom-SCCRR and cannot be reproduced without permission. Quotations from it should be acknowledged to Shalom-SCCRR

References

Marsabit County Integrated Development Plan 2018–2022. https://maarifa.cog.go.ke/resource/cidp-marsabit-2018-2022.

Saferworld. (2015, June 19). Marsabit County Conflict Analysis. Saferworld. https://marsabit-conflict-analysis%20(2).pdf.

Security Research and Information Center (2014). The Northern Frontier: Nature and Conflict Dynamics in Marsabit County. Nairobi: SRIC Publisher.

Shalom-SCCRR (2019, January 7). Shalom-SCCRR continues to Promote Peace and Development in Marsabit. SHALOM-SCCRR CONTINUES TO PROMOTE PEACE AND DEVELOPMENT IN MARSABIT

By Asha Said Awed , MA,

Program Assistant ( Nairobi, Marsabit & Turkana-West Pokot Projects)

Shalom Center for Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation