(Shalom-SCCRR Department of Research

Director: Prof. W. K. Omoka.

The voice of Peace Practitioners and Researchers)

PERSISTENT INTER-ETHNIC HOSTILITY AND ITS IMPACT ON SOCIO-ECONOMIC LIVELIHOOD ALONG KISUMU-NANDI BORDERLINE {© 2020 Shalom-SCCRR}*

By Arthur Magero Abonyo, MA.

(Peer-reviewed by Prof. W. K. Omoka, Rev. Dr. Patrick Devine, and Shalom-SCCRR Dept. of Research)

Introduction

Hostility among ethnic groups straddling the borderline of Kisumu and Nandi counties has evolved into a very devastating phenomenon to both the people and their livelihood opportunities. The hostile relationship between these communities has often manifested itself in intolerant attitudes and behavior and often very violent actions. Other than undermining the social fabric which is the bedrock of intercommunal cooperation for growth, the hostile relationship has resulted to devastating effects on the socio-economic livelihood of individuals and the communities along the borderline. The persistent hostile relationship is linked as an effect to antagonists being actuated by selfish interests or concerns on the one hand, and on the other hand being disposed to view or treat the neighbouring ethnic other (Luo/Nandi) as an object of cynicism, mistrust, and hatred. Moreover, the resident communities have constantly lost opportunities for economic growth as violent flare ups result into massive destruction of food crops, loss of livestock and disruption of trade as markets become inoperable and roads impassable.

In operationalizing its conflict intervention methodology, Shalom-SCCRR holds the central notion that continued research and conflict analysis is imperative to the activation of sustainable conflict transformation interventions. To this end, Shalom has for the past 1 year been engaged in collecting data related to conflict situations and peacebuilding interventions along Kisumu-Nandi border. The longitudinal approach to data collection and analysis has been aimed at improving the verifiability of the underlying causes and dynamics of conflict along this volatile borderline consequently improving awareness and supporting conflict sensitive programming among stakeholders, peacebuilding practitioners and the general public. This data has since been subjected to analysis and the findings are presented descriptively in the sections below.

Context of the conflict

Kisumu and Nandi Counties share a stretch of about 103 km borderline along Tinderet Sub-county in Nandi County and Muhoroni Sub-county in Kisumu County. There are predominantly two tribes that stay along this borderline; the Nandi and the Luo. However, there are a few other tribes such as the Luhya, Kisii and Kikuyu who stay and work along the boundary; all totaling to about 75,420 people that is 54,423 from the Nandi side and 20,997 from the Kisumu side (KNBS, Kenya Population and Census 2009). The borderline conflict mainly involves the Luo and the Nandi ethnic groups who reside within an area of about 185.50 km2 in Muhoroni Sub-county (CIDP Kisumu County, 2018) and 321 km2 in Tinderet sub-county (CIDP Nandi County, 2018). This gives to a total area of 506.50 km2 affected by the conflict along the Kisumu-Nandi borderline.

Kisumu-Nandi boundary line is part of the larger Western Kenya sugar belt. Consequently, sugar cane farming is the mainstay of people’s economy as well as a major point of controversy between both sides of the ethnic divide. The prolific nature of land in this region coupled with the vast estates under the highly valued sugarcane crop has constantly defined the contestations between the two communities over the exact location of the boundary that divides the two counties. The boundary contest has recently brought into question the legitimate ownership of the major sugar factories (Chemelil, Muhoroni and Miwani) which are located in very close proximity within the border and which serve the needs of both communities.

Apart from sugarcane farming, communities also engage in Livestock keeping. The Luo people tend to rear larger herds of indigenous cows while the Nandi rear exotic breeds that are also fewer in number.

In its conflict mapping exercise conducted in 2018 along the borderline, SCCRR established that this conflict is contextualized in 9 villages which also double up as the key hotspots. They are Kibigori, Songhor East, Songhor West, and God Abuor from Kisumu county and Chemelil, Chemase, Songhor, Soba, and Kapkitony from Nandi county (Shalom-SCCRR Conflict Mapping Report, 2018).

Increased occurrence of conflict incidences along Kisumu-Nandi borderline has historically been associated with political seasons particularly since the onset of multiparty politics in Kenya in 1992. However, cases of land invasions and livestock theft do occur even out of political seasons especially when particular triggers are experienced in the community. With the border created as a settlement area under land settlement programme, majority of land occupants are both squatters and genuine buyers. The borderline exhibited livestock related conflicts even though the communities often resolved them with ease. Nevertheless, the multi-party politics exercabated the tensions resulting in more frequent disputes along ethnic lines (Oucho, 2002).

The conflict situation along this volatile borderline has always changed during political seasons and it gets worse when either of the two communies are in different political parties or sharing different political ideologies. For instance, the fallout between political factions in 2009 further divided the two communities (CHRIPS, 2016). Furthermore, during the political seasons, the communities have used livestock theft, disputed land boundaries and ethnic differences to articulate their hostility towards enemy community.

Conflict and its impacts on Socio-economic livelihood of the people

Inter-ethnic hostility in Kisumu-Nandi borderline has often manifested itself through inter-ethnic attacks, political violence, sporadic livestock theft and encroachment into private land. These violent manifestations are widely seen by community members as the major enablers of the fragility that time and again characterize inter-ethnic relations along this borderline.

The unstable relations between communities and the resultant hostilities have had far reaching effects on the socio-economic livelihood of the entire population along the borderline. Shalom-SCCRR’s conflict monitoring report 2019-2020, indicates that among the major effects of the manifest violent incidences along Kisumu-Nandi borderline are deaths, injuries, forced migration, destruction and loss of property. In the past one year 14 cases related to destruction of property were reported, 6 cases of livestock theft, 7 injury cases and 3 cases related to massive displacement and migration of families along the borderline were reported (SCCRR, 2019).

Correspondingly, the conflict has stagnated the socio-economic development as manifested by the sporadic closure of markets, schools and health facilities. On average, an eruption of conflict between the two bordering communities leads to the total closure of 5 markets, 27 schools and 11 health facilities. These facilities under normal operation supports the livelihood of an average of 8,000 people of both Luo and Nandi origin who reside in the 2 bordering sub-counties.

Being a highly agricultural region, farms have often been a ready target for violent groups when expressing vengeance against the ethnic other. Violent interethnic attacks have more often than not been associated with the burning of sugarcane plantations, destruction of homes and stealing of livestock.

As existing communities whose livelihood largely depend on agriculture, the amount of loss in the livestock population as a result of theft and the destruction of huge acres of farmlands points towards significant loss of the much needed income. Furthermore, the violence that was associated with the 2017 electoral process was accompanied by the destruction of more than 200 acres of sugarcane plantations that would have otherwise been harvested and sold to the 4 sugar processing factories that are located along the borderline.

Causes and parties in the conflict

Shalom-SCCRR’s analysis of the Luo-Nandi conflict and its causes indicate that the occurrence of land related conflicts was higher in frequency compared to the other 3 manifestations of conflict; interethnic attacks, political violence and livestock theft (SCCRR, Conflict Monitoring, 2020). It can be argued convincingly that the frequent occurrence in land based conflicts is a pointer towards existing challenges around land use and access. In his understanding of environmental security as the freedom from environmental destruction and resource scarcity, Gleditsch develops a nexus between resource scarcity and conflict which is applicable in the analysis and understanding of land scarcity as one of the underlying causes of conflict in the Kisumu/Nandi borderline. Basically, his perspective contends that there are three main forms of resource scarcity; “Demand induced scarcity, which results from population growth; supply induced scarcity, which results from the depletion or degradation of a resource and structural scarcity, which refers to the inequality in distribution of the resource” (Gleditch, 2015). In the Kisumu/Nandi case, structural scarcity seems to be the most dominant form of scarcity that is associated with the prevailing inter-ethnic conflict.

While the vast majority of people in the borderline depend on livestock rearing and crop production for livelihood, there is only minimal quantity of land that is available for the majority population. While each household on either side of the borderline owns an average of 2acres of land, there are a few richer and power bearing individuals within the same locality who own bigger tracts of land which often lie idle. The disparity in land ownership frequently sparks incidences of land invasion whereby those who are deprived of sufficient arable and grazing land encroach into the vast privately owned idle lands to either plant crops for subsistence or graze their livestock. Land invasions have widely been ethnicized and used to contribute to the strengthening of ethnic identities and ethnic conflict.

Contested land tenure systems and the resultant conflicts have been exacerbated by the inadequate institutional infrastructure for conflict response. Institutional deficiencies and the associated lackluster response by security apparatus have been key contributing factors to the run-away insecurity, lawlessness and less motivation among community members to take action against conflict perpetrators. These factors have created tenacity of ethnic hostility verging on hatred that has undermined adaptation to peaceful co-existence between the Luo and Nandi communities. The existing structural deficiencies among local institutions has made it impossible.

On the same note, the non-responsive security agents have given youths and business people from both communities room to be involved in the sporadic livestock theft that has played out in the conflict between the Luo and Nandi communities living along Kisumu-Nandi border. Based on the conflict monitoring data for 2019-2020 from (Shalom-SCCRR’s Conflict and Peace Monitoring System) 33% of conflict incidents reported were on livestock theft carried out by groups of youth characterized by their ethnic affiliation. From the Shalom-SCCRR field research, it was established that lack of proper functional state security along the border has contributed to the continuity of the conflict. Low employment especially among the youth, cultural beliefs (that one community is culturally and traditionally the custodian of livestock keeping), the emerging commercialization of livestock theft are other causes to the conflict between the Luo and Nandi community as a result of dysfunctional governance structures. Hence elders and business people from both communities playing out as spoilers to the conflict as their intension is to benefit from it.

The state of lawlessness experienced by the two communities along the border of Kisumu-Nandi has created a sense of hatred characterized with violence and corruption. This has seen an increase in cases of insecurity characterized with criminality (livestock theft), corruption and cartels where business people have taken advantage of the stolen livestock hence driving the conflict between the Luo and the Nandi communities. On the same note polarized political seasons have seen the two communities end in violent conflict with the youths and politician taking the frontline as actors to the conflict. Indeed, political incitement with incendiary speech, ordinary crimes and hateful rhetoric have been key triggers to inter-ethnic conflict at the Kisumu-Nandi border. This has seen the communities face cycles of attacks and counter attacks due to the ineffectiveness of governance structures hence putting the communities along the border in a hostile situation characterized with enmity and revenge. However, the local administrators, church leaders and elders have shown up as peace agents to the conflict.

Historical contestation of land distribution is another underlying cause of conflict between the Luo and the Nandi community living along the Kisumu-Nandi border. The case of land encroachment has led to persistent inter-ethnic hostilities at this volatile border with elders and youths as the primary perpetrators. The demands by the encroaching community have always based on injustices they have been facing with majority of them living as squatters. This has created hostility as each community demands ownership of land along the border. This has been politicized and politicians have been beneficiaries in the conflict while leaving the communities in dilemma over the unresolved cases of land encroachment. As Kanyinga Karuti puts it, high population coupled with a change in land tenure has offered a great challenge for people given the job of ensuring that people own land (Kanyinga, 2000).

Furthermore, lack of enough arable land has often exacerbated the inter-ethnic conflict along this borderline. Such that the reduced acreages of arable land along the border is forcing the communities, with their elders and youths as primary actors to encroach into idle private land for farming and grazing their livestock. This has been a trigger factor of this conflict between the two communities. Though encroachment has been a way of raising their grievances to their leaders and especially during the electioneering period, youths have taken advantage of land encroachment to make attacks and counter attacks as a way of keeping their enemy at bay. According to the groups engaged by Shalom-SCCRR along the Kisumu-Nandi border, they noted that by and large, at least 2-3 cases of encroachment are reported every year but during the electioneering period the cases are sporadic.

More so, the appropriation of land belonging to Luo and Nandi communities along this border has been tied on shift of the boundary and ownership of big pieces of land by political leaders along the border. This blame has been put on the post-colonial regime that adopted the colonial system of land distribution hence the contributing factor to hostilities experienced along the Kisumu-Nandi border as it has infringed on their property right (Koissaba, 2016).

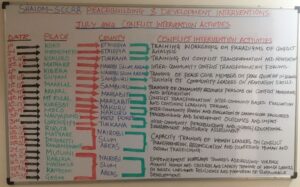

Shalom-SCCRR Intervention Strategy and Impact

Rebuilding the relations of communities living along the Kisumu-Nandi border has been a process where Shalom-SCCRR has journeyed with a group of key influential opinion shapers from both Kisumu and Nandi counties along the volatile border. The Shalom-SCCRR methodology of intervention along this volatile border is unique in the sense that the participation of the community is a key component of the intervention strategy. The focus of the intervention is based on building skills and capacities of the communities in peacebuilding, establishing of community organization/structures of response, enhancing community local-government collaboration and dialogue.

For the success of the intervention, Shalom-SCCRR has been working in close collaboration with the government, local interreligious institutions, and ethnic groups’ influencers. This collaboration has led to the establishment of 2 local peace committees, abetted by Shalom-SCCRR, each having 40 influential ethnic leaders. The 2 committees from both Nandi and Kisumu sides of the conflict divide have the mandate of initiating peaceful means of conflict resolution and working closely with ethnic groups to facilitate mediation and negotiation interventions (Okoth, Wamae, Serem, & Magero, 2019).

The community conversation approach which calls for community participation provides the platform for members of the affected population along the border to be heard, hence empowering them to be part of the decision-making processes as well as taking a direct action on conflict management issues. Similarly it has provided the ethnic groups with the opportunity to come together to negotiate about the underlying causes of their conflict and stagnant local economy. The active involvement of the community would enable them to develop effective strategies in addressing conflict issues and implementing actions to transform their situation. In fact the two communities have been identifying changes they need to introduce into their value system through their participation in conflict preventive initiatives under the guide of Shalom-SCCRR. More so, constant meetings between leaders from the two ethnic communities has bolstered the relationship between them at the Kisumu-Nandi border. On the same note the trained group of local community leaders and facilitators from both ethnic communities have continuously empowered community groups with conflict interventions skills and knowledge. Coupled with the field monitoring system under Lead Community Facilitators (LCFs), the two communities have been able to track conflict incidences, intervention to the conflict, impact and the change noticed in rebuilding their relationship.

The establishment of a mechanism for supporting interethnic schooling has boosted the level of relationship along the border. It is important to note that, currently, the tribal groups that were once fierce rivals are steadily becoming architects of the change they would like to see and the development that they desire for themselves and their future generations (SCCRR Workshop Report 2019). Indeed, the reduction in reported cases of livestock theft and embracing of community conversation-dialogues in addressing conflict issues, has brought life along the border with the communities freely interacting and doing business together. On the other hand “the schools have provided a conducive learning environment for the young generation and has helped inculcate a culture of peace through enhancing ethnic tolerance.” (Okoth, Wamae, Serem , & Magero, 2019).

Shalom-SCCRR in its intervention has mapped out schools affected by the conflict along the border of the 12 most vulnerable schools, Shalom-SCCRR has engaged 8 out of the 12 which is equivalent to 67% percent with development projects. Some of these schools include: Chepsweta primary school, Kalyet Primary school, Kipsisiin Primary School and St. Peter’s Soba mixed secondary school from Nandi county and Nyang’ primary school, Songhor Primary school, Onenonum Primary school and St. George Wuok primary from Kisumu county. Through its peace education and development programs, Shalom-SCCRR has invested in improving the structures and providing learning materials in these schools. Cultivating the ethnic balance in these schools is also key in ensuring there is good inter-communal relationship. In addition to that, it has engaged teachers and pupils in implementing peace education training curriculum to the pupils and formation of peace clubs for easy implementation.

Conclusion

Kisumu-Nandi border inter-ethnic conflicts have negatively impacted the socio-economic livelihood of the people. The conflict had caused division among the communities living along the border thereby making their relationship sour. The villages along the border line and institution have suffered socially and economically as the antagonism between the Luo and Nandi along the border persisted. The major causes to this antagonism has been dysfunctional governance structures and historical contestation of land manifested in ethnic hatred, sporadic livestock theft and disputed land ownership linked to political incitement. Analytically it has been understood that the conflict along the Kisumu-Nandi border has often escalated during the electioneering years. This has a clear indication how political realm has been used to trigger violence along the border.

However, the desire of these communities to start interacting and relating in a manner that indicate peaceful coexistence is not easy. The professionalism of Shalom-SCCRR personnel stepped in to help rebuild the relationship between the communities along the Kisumu-Nandi border. Shalom-SCCRR sees the need to build the capacity of the local leaders and peace actors with conflict prevention, conflict management and conflict transformation skills. It has also continuously involved them in active peacebuilding initiatives as a way to rebuild their relationship and hence creating room for improvement in their socio-economic way of livelihood as it has helped in bringing the communities together. The need to support schools along this border was also vital in cultivating ethnic balance and ensuring that children learn in a peaceful environment with good structures and learning materials. Shalom-SCCRR rose to the task in collaboration with the local communities. Peace education has also been presented using Shalom-SCCRR syllabus to schools along the border hence cultivating a culture of peace in younger population.

* This document is copyright to Shalom-SCCRR and cannot be reproduced without permission. Quotations from it should be acknowledged to Shalom-SCCRR

REFERENCES

CHRIPS. (2016). Conflict Assessment Report:Danida Peace, Security and Stability (PSS) Programme-Kenya 2016-2020. Nairobi: CHRIPS.

CIDP Kisumu County. (2018). County Government of Kisumu: County Integrated Development Plan .

CIDP Nandi County . (2018). County Government of Nandi: County Integrated Development Plan 2018-2023.

Gleditch, N. P. (2015). Pioneer in Analysis of War and Peace Vol. 29 Oslo: Spring International Publishing.

Kanyinga , K. (2000). Redistribution from Above: The politics of land rights and squatting in coastal Kenya Vol 115. Nordic Africa Institute, 619-638.

KNBS, Kenya Population and Census 2009, https://www.knbs.or.ke/?wpdmpro=2019-kenya-population-and-housing-census-volume-i-population-by-county-and-sub-county

Koissaba, B. O. (2016). Elusive Justice: The Maasai Contestation of Land Appropriation in Kenya: A Historical and Contemporaty Perspective.

Okoth, G., Wamae, J., Serem , R., & Magero, A. (2019, September 5). Post-Conflict Reconciliation along the Kisumu/Nandi Border: Shalom-SCCRR Leads the Mediation Intervention, https://shalomconflictcenter.org/post-conflict-reconciliation-along-the-kisumu-nandi-border-shalom-sccrr-leads-the-mediation-intervention/

Oucho, J. O. (2002). Undercurrents of Ethnic Conflict in Kenya . London: Brill Laden Boston-Koln.

Powell, L. H., & K, W. (2007). Hostility . New York: Research Gate.

Shalom-SCCRR. (2019). Conflict Incident Tracker Tool. Unpublished manuscript.

Shalom-SCCRR. (2018). Conflict Mapping Workshop Report. Unpublished manuscript.

Shalom-SCCRR (2017). Kisumu-Nandi Border Project Design. Unpublished manuscript.

By Arthur Magero Abonyo, MA,

Program Officer (Kisumu-Nandi & Nakuru Projects)

Shalom Center for Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation