‘‘Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this rights includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.’’

Article 18 of Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Religion is one of the most prevalent institutions in society. Central to all religions are concepts concerning ‘the Divine’, creation, life’s essence and existence, peace, truth, justice and mercy, among others. Religions can contribute to conflict transformation and peace-building in numerous ways, especially by promoting tolerance and reconciliation. This requires developing dialogue and cooperation, influencing moral and ethical-climax, enabling the weak and fearful with authorative voice, developing cooperation, providing humanitarian interventions and altruistic assistance amid other dimensions.

However, according to Devine (2011 and 2017), when religion becomes disproportionately energised by increasing quantitative institutional membership, to the detriment of qualitative spiritual transformation, the potential for it to become a destructive factor generating conflict escalates. It is within this context that the propagation of religions as mere institutions becomes the primary focus, rather than the fulfilment of their core spiritual message with respect to peace, truth, justice and mercy. The core spiritual message of religions should never be forfeited or compromised to satisfy the insidious interests of religions leadership or its institutional socio-political ends.

The religionization of politics and the politicisation of religion have far reaching negative implications on the process-deterioration of tolerance to intolerance. He maintains that this process is primarily evidenced in the emergence of negative radicalized fundamentalism. This form of fundamentalism can further deteriorate to non-violent extremism evident in the unwillingness to dialogue and in attempts to prohibit freedom of expression of alternative perceptions. An additional deterioration of non-violent extremism results in manifest violent extremism, operationalized in terroristic acts, aimed at purging society of those advocating contrary beliefs and positions on issues’.

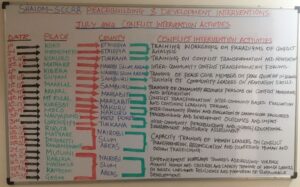

Shalom-SCCRR’s intervention in Nairobi County involves insertions into three major urban informal settlements: Mathare, Kariobangi and Kibera. These areas are marginalized, submerged with poor infrastructure, social exclusion and economic stagnation. The bulk of the youth population in the county is located in these disadvantaged locations. Kariobangi and Mathare are central areas of inter-religious and inter-ethnic violence and criminality that leads to appalling loss of lives and destruction of property. SCCRR has managed to train and equip 140 stakeholders (men, women, youth, religious leaders and local administrators) conflict transformation expertise. This entails empowerment with analytical skills and peace building techniques oriented to addressing inter-ethnic and inter-religious conflict drivers. The interventions have used a sensitive participatory approach to facilitate conflict actors to meet in ‘safe spaces’ to break down barriers to peaceful coexistence.

Recently, an inter-religious conflict occurred in Kiamaiko (Kariobangi). The major religions in this area are Islam and Christianity. The conflict orbited around two warring religious groups of the Burji community (Christians and Muslims). Each religious faction has strengthened their superior attitude and dominance over the other and this has translated into manifest violent conflicts. The clashes were over the right to conduct night prayers among the two religious groups that resulted to: mosques destroyed, two churches torched, scores injured and one dead. The community’s identity construction and group interests fuelled and escalated the inter-religious conflict.

The stakeholders group, trained by Shalom-SCCRR, intervened by engaging in consultations oriented to a ‘dia-praxis’ interventions (Devine, 2017) motivating Christian and Islamic leaders to promote reconciliation among the two groups. This involves not just dialogue but also engaging in joint development activities. The inter-religious dialogues discussed at length the role of religious leaders in conflict and reconciliation – both individually and collectively.

Joint action plans were developed based on the need for communities to be enlightened that religion should not only be a tool of tolerance but should also foster positive peace and sustainable development in the area. The local community administration of Kiamaiko acknowledged the groups valuable efforts while also challenging other State institution to become more proactive and improve the levels of human security in the area.

SCCRR is devoted and will continuously enhance the capacity of religious leaders and their followers in informal settlements to incorporate mind-sets of inclusivity, vibrant diversity, equal dignity and peaceful unity in living together.

By

Joyce Wamae Kamau, MA, BA, Program Manager (Peacebuilding & Development, Urban Settlement Program)

Asha Awed Said, MA Candidate, Program Assistant (Samburu & Nairobi Projects)