By: Prof. W. K. Omoka, PhD

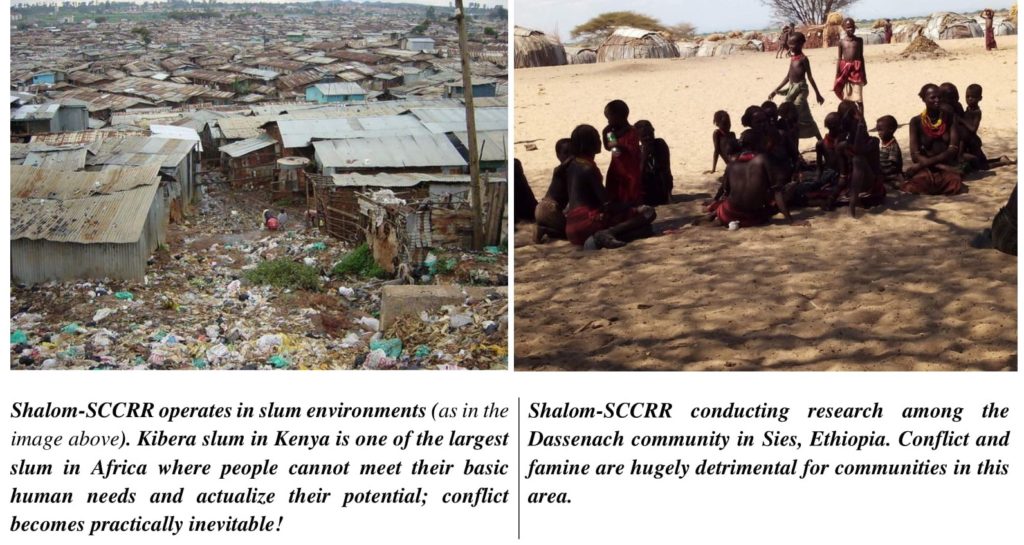

The accomplishments of Shalom-SCCRR below are an important practical contribution to peacebuilding between ethnic communities and groups in the margins of their national society. Specifically, those who live in physically harsh (arid and semi-arid) environment and those who live in very poor and crowded areas in cities/towns (i.e. slums and the like).

Locals of harsh environment along with residents of slums and the like face considerable challenges of getting the basics of life. Some of the challenges translate to inter-communal conflict in the harsh environment, and inter-group conflict in poor and crowded areas of cities/towns. These people, like others in the national society, have different identities; some of which contribute to informing, generating and maintaining the conflict’s dynamics. Ethnic category — a quality, not quantity — is one of them. It does not directly bear on inter-communal/inter-group conflict, but it is pivotal in accounting for the conflict; it is among the key factors in understanding the conflict’s dynamics.

Outputs/Results for January 2020-June 2021

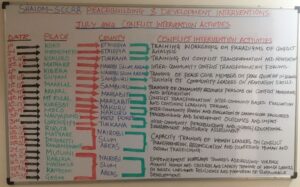

- 28 significant Shalom-SCCRR established peace groups of influential opinion shapers received workshops on conflict transformation and peacebuilding training.

- 3,493 Key Peace Stakeholders (women and men) in inter-communal peace were given training in detecting hostile intentions in the behavior of community other along with techniques of conflict transformation.

- 219 Shalom-SCCRR empowered community facilitators and resource persons, implemented conflict transformation and peacebuilding interventions in 28 conflict environments.

- 23 Shalom-SCCRR supported peace and conflict monitoring mechanisms: operational and providing key data applied in the design of local conflict interventions (ranging from conflict prevention, management, resolution and transformation.

- 24 Conflict Negotiation and Mediation forums implemented with grassroot communities.

- 53 Shalom-SCCRR funded School/Educational development projects benefiting 17,931 boys and girls marginalized by cultural practices, conflict and poverty.

- 30 Health centers located in poor and marginalized locations provided with medical and Personal Protective Equipment to counteract the spread of Covid-19.

- 32 professional health care personnel, working in conflict zones, trained on Covid-19, its prevention, information dissemination, and management mechanisms through Shalom-SCCRR funded workshops.

- 2 Children Rescue Centers were given assistance of food along with education/learning materials, and the like.

- Funded human trafficking interventions.

- Shalom-SCCRR Peace Education Syllabus implemented: benefiting more than 17,828 pupils and students in primary and secondary Schools respectively.

- 45 Shalom-SCCRR established and supported SHALOM Peace Clubs, implementing conflict transformation activities in areas affected by inter-ethnic conflicts/religious ideological extremism and marginalization.

- 6 project areas supported with mechanisms for augmenting Shalom Peace Clubs in addressing potential/manifest localized inter-communal conflict and countering/attenuating violent conflict risk of religious extremism.

Shalom-SCCRR’s intervention in the conflicts – evidenced here by the accomplishments in question — is informed by research-based understanding of the conflict’s patterns and dynamics. Ethnic category being a key factor in understanding the conflict stems from the fact that it is essentialized in the context of the conflict. This is explained below.

Essentialization is invariably about difference. Essentializing of the ethnic category is when people in the same category are all held to share the same essential quality, their “…ness” — e.g., “Turkananess”, “Dasennechness” — which makes them to be what they are and different from any one else. From the essentialization perspective or standpoint, ethnic categories exist apart from any process and cannot be provisional; they are objective categories of real differences among people. Thus, for example, in IGAD countries region of social formations of pastoralism a Karamajong (Uganda) or a Nyangatom (Ethiopia) or a Samburu (Kenya) or a Toposa (South Sudan) is seen as a member of a category, not as an individual. Essentializing ethnic category — an identity mark — is pervasive in the region. Now, because conflict between communities/groups invariably stems from difference over something/issue, it follows that essentializing of ethnic category is a recipe for intercommunal/intergroup conflict. And, of course, conflict is inimical to development (= getting education, having medical care, eating healthy diets, having long-lived lives, living in sanitary environment, being in a state of wellness physically, mentally and socially simultaneously). Development by criteria of the foregoing is quite beyond the reach of the overwhelming majority of people who live in the margins of their national society.

Essentialization of ethnic category is much associated in a causal sense with inter-communal conflict within the geographical confine of the social transformation of pastoralism in the countries of intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). The fact of ethnic category being essentialized is among the impediments to inter-communal peace coexistence.

Essentialization of ethnic category is much associated in a causal sense with inter-communal conflict within the geographical confine of the social transformation of pastoralism in the countries of intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). The fact of ethnic category being essentialized is among the impediments to inter-communal peace coexistence.

Shalom-SCCRR’s peace building efforts (initiatives and activities) includes addressing essentialization of ethnic category by building intercommunal social capital. Social capital is relational social networks between individuals of social units based on mutual trust and information exchange advantageous to network members. Inter-communal social capital is functional for intercommunal peace precisely because it counteracts distrust between communities thereby contributing to peace building.

There is a clear difference of variability in terms of obtaining the means of sustaining life in urban locations (slum and the like) on the one hand, and rural physically harsh environments on the other hand. Research by Shalom-SCCRR has found that the probability of a conflict incident occurring is high in the physically harsh environment – inhabited by pastoral communities – and low in city/town areas where the poor live in crowded space. Of course, the conflict, as pointed out earlier, is related directly or indirectly as an effect to sustaining life in one way or the other. The conflict risk of earning a living or sustaining life is high in the physically harsh environments and low in city/town areas where the poor live in crowded space. This is because in the city/town there is a wide range of ways of earning a living, and none of the ways is invariably predominant in space or time, whereas in physically harsh environments there is by and large one source of earning a living, namely pastoralism. Conflict in the physically harsh environment is typically linked as an effect to pastoralism by virtue of pastoralism being the predominant way of sustaining life. It follows, therefore, that spreading the conflict risk of depending mostly on pastoralism for sustaining life — that is, breaking up pastoralism’s virtual monopoly of the conflict risk – should lead to decrease of inter-communal conflict occurrences that stem from dependence on pastoralism for sustaining life. In this connection, Shalom-SCCRR addresses the conflict risk of depending mostly on pastoralism for sustaining life through on-the-ground working with locals in the project areas to diversify ways of sustaining their lives away from pastoralism. This not only contributes to peace building but also decreases the probability of starving in the event that locals’ herds die in large numbers due to prolonged drought and epidemic disease.

By

Prof. Wanakayi K. Omoka PhD, Shalom-SCCRR Director of Research

(As presented by Prof. Omoka to Ms. Esther Kibe MA, Shalom-SCCRR’s Communications Department shortly before his passing on)

Relevant Links to some articles associated with the late Prof. Omoka, RIP

- https://shalomconflictcenter.org/shalom-sccrr-honours-the-life-of-prof-wanakayi-k-omoka-rip/

- https://reues1ugycb1x7ih3u7oilyn-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/AN-UNDERSTANDING-OF-THE-WORK-OF-SHALOM-SCCRR.pdf

- https://shalomconflictcenter.org/human-rights-are-a-foundation-of-shalom-sccrrs-conflict-resolution-and-reconciliation-interventions-2/

- https://shalomconflictcenter.org/2010-2020-shalom-sccrr-results-and-achievements/

- https://shalomconflictcenter.org/2020-shalom-sccrr-peacebuilding-and-educational-health-development-achievements/

- https://shalomconflictcenter.org/shalom-sccrr-peace-and-development-outputs-during-2019/

- The Voice of Peace Practitioners and Researchers in Africa: Briefing Papers. Shalom-SCCRR Director of Research: Prof. W. K. Omoka. – Shalom Center for Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation | SCCRR (shalomconflictcenter.org)

- https://shalomconflictcenter.org/shaloms-conflict-transformation-and-peacebuilding-metrics-a-brief-overview/

- https://shalomconflictcenter.org/shalom-sccrr-collaborates-with-the-queens-university-of-belfast-edward-m-kennedy-institute-for-conflict-intervention/

- https://shalomconflictcenter.org/peacebuilding-and-conflict-behaviour/

- https://shalomconflictcenter.org/coronavirus-covid-19-a-communication-from-the-shalom-center-for-conflict-resolution-and-reconciliation-shalom-sccrr/

- https://shalomconflictcenter.org/shalom-sccrr-international-chairman-fr-patrick-devine-appointed-to-council-of-tangaza-university-college-2/

- https://shalomconflictcenter.org/persistent-conflict-between-the-pokot-and-the-turkana-causes-and-policy-implications/