‘UNSC1325 asserts that women must be participants in peace processes and peacebuilding, yet they continue to be largely absent. Do you agree or not that it is important to include women – and if so, how can this happen’

(Her recent Term Paper submitted to the University of Dublin Trinity College, Irish School of Ecumenics)

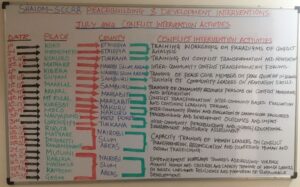

(Photos below are added from Shalom-SCCRR’s Peacebuilding work in East Africa)

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 1325 of 2000, was the first time the United Nations addressed the unique impact of armed conflict on women. By focussing on women in the context of peacebuilding, Resolution 1325, hereafter referred to as 1325, asserts that peace and peacebuilding are gender-nuanced and thus to achieve sustainable peace, gender must be a factor. 1325 and subsequent resolutions, 1820 (2009); 1888 (2009); 1998 (2010); 1960 (2011); 2106 (2013; 2122 (2013); 2242 (2015), and 2467 (2019), recognised that peace and security efforts are more sustainable when women are equal partners in the prevention of violent conflict, and that the contributions women make to conflict resolution and peacebuilding are undervalued. Despite the intentions of 1325, 19 years later women are absent from peace processes and peacebuilding. This essay starts with a critical examination of the intentions of the resolution and highlights some of its shortcomings. In agreement with the intentions of 1325, this essay argues women have a right to be at the peacebuilding table, it gives reasons for this position, and it suggests wide-ranging ways this can be put into practice, both formally and informally.

Although 1325 set out to ‘[m]ainstream gender in peacebuilding’, this essay suggests that in addition to the failing of the international community to get women to the peacebuilding table, there have also been shortcomings in its interpretation of the underlying concepts of peace and conflict at the heart of 1325. The second section, consequently, makes the case that a feminist perspective on peace and conflict is necessary to develop a deeper vision of a peace which can be sustainable. In the pursuit of this sustainable peace, a concept at the core of 1325, the difference between positive and negative peace is explored and this essay will examine how a focus on achieving negative peace, i.e. cessation of armed conflict, does not ensure a positive peace, with social justice and equality for all. This section advocates that the traditional, narrow definition of conflict, as armed conflict, is challenged and broadened, to reflect the differing gender hierarchies and power inequities experienced by women in the form of structural violence. Additionally, this section will explore how this structural violence in societies is manifested in the continuum of violence women experience, pre, during and post-conflict. This violence, embedded in many patriarchal cultures, hinders social harmony and progress for all genders in the aftermath of conflict.

As will be shown in the third section, it is these feminist perspectives on peace and conflict, rather than merely having quotas of women involved, which ought to be the focus of any peacebuilding process. Traditionally gendered processes, peacebuilding efforts often mirror the gendered inequities in existence in societies prior to the conflict. Thus, for a process to be successful, recognising women and girls’ experiences, including their local contributions to peace, is essential. 1325 has both qualitative and quantitative targets, but by focussing on getting numbers of women involved in peace processes and around the peacebuilding table, the international community does itself, peace efforts and women, a disservice. Too much focus (with limited success) has gone into a bean-counter approach to the inclusion of women at this critical stage of rebuilding societies. This essay argues we should take a more holistic approach to gender and peace, by going beyond merely adding numbers of women to the making of a negative peace process. It suggests we address the profound structural violence women experience, in order to achieve a fusion of negative and positive peace which is more likely to be a sustainable peace To do this, there would have to be a paradigm shift in the approach taken by international agencies tasked with delivering on 1325. A shift from a focus on gender as being women only, to all genders; from stereotyping women as victims to valuing them as participants, and from merely the ‘return to the way things were’, before the conflict, to the rebuilding of a just and equitable society.

1325 – Putting women at the Peacebuilding table

1325 was the first resolution to recognise that there was ‘the need for and contributions of half of the world’s population to international peace and security’ (Naraghi Anderlini & Tirman, 2010). It also advocated for the protection of women and children after a conflict, urging parties to prevent gender-based violence and to prosecute those responsible for, amongst other crimes, crimes of sexual and other violence against women and girls (United Nations Security Council, 2000). It called on member states to qualitatively adopt a gendered perspective at both decision-making stages, and during peacebuilding initiatives. Quantitatively, 1325 called on conflict parties and UN peacekeeping actors to increase numbers of women involved at all levels, including at a community level. However, as far as participation in peacebuilding is concerned, the reality has been very different from the rhetoric (Kaufman & Williams, 2018, p. 2). The 2015 UN Global Study on the Implementation of 1325, noted ‘of the 31 major peace processes between 1992 and 2011, only 9% of negotiators were women’; fewer than 3% of signatories to peace agreements are women; and it was only in 2013, Mary Robinson, the former Irish President, was appointed the UN’s first woman lead mediator (UN Women, 2015).

Amongst the criticisms of 1325 are the fact that its use of language reflects essentialist stereotypes of both men and women, women as victims and as peacemakers; men as aggressive and sexualised (despite some references to the roles some women play as combatants). In addition, success has been hindered by a lack of accountability and monitoring (Bosetti & Cooper, 2015), and a lack of funds in support of peacebuilding projects to addresses gender equality (Bosetti & Cooper, 2015). Some feminist scholars have reflected that it is ghettoizing women away from the UN’s core security agenda, thereby hampering any chance of the mainstreaming of gender equality (Shekhawat, 2018, p. 9), and crucially, 19 years later there is continued male domination of all significant international and national institutions within the UN.

Why should women be included in peacebuilding?

Many advocates for women’s participation have taken a rights-based approach, asserting that it is a matter of justice, and as women make up half of the world’s population, they should participate in any decisions which will affect their lives. In (Naraghi Anderlini, 2007), Sanam Naraghi Anderlini writes, they have an inalienable right to be active and contribute to ‘decision making that affects their world, countries, communities, and families’. However, the problem with this approach, as can be seen with the slow progress in its implementation, is that many actors in this area remain unconvinced of the value that women’s participation may bring and ‘fear it may derail the process’ (O’Reilly, et al., 2015, p. 2). So, if the justice argument is not enough, the nature argument suggests further evidence.

In his book ‘The Better Angels of Our Nature’, Pinker asserts that ‘over the long sweep of history, women have been and will be a pacifying force’ (Pinker, 2012). However, arguing for women’s inclusion in peacebuilding, merely based on their perceived, more peaceful nature, may lead to continued stereotyping of women, perpetuating gender inequality and preventing necessary transformative societal change. It also fails to acknowledge contemporary feminist thinking, which asserts that ‘male and female values are socially constructed…’ (O’Flynn & Russell, 2011, p. 41) and therefore one cannot make homogeneous, gendered assumptions about responses to conflict.

Notwithstanding criticisms of the stereotyping of women’s peaceful nature, there are real success stories of women’s contributions to peacebuilding processes. A 2015 Report from UN Women reported, ‘Women’s participation increases the probability of a peace agreement lasting at least two years by 20%, and by 35%, the probability of a peace agreement lasting 15 years (UN Women, 2015). In addition, in a multi-year Research project, which covered 40 peace negotiation case studies, it was found that the chances of a final agreement were much higher if women’s groups had a strong influence (Paffenholz, et al., 2016).

Challenging the perceived homogeneous nature of women, necessitates we recognise women are not always the victims. At the DDR (disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration) stage, it should be recognised that it is not only men who are the perpetrators of the violence. Women are also combatants and perpetrators, ‘… ranging from forced participants – often as a result of abduction, as dependant followers of fighters, in assisting fighters, and shields…’ and as active combatant soldiers ( United States Agency for International Development (USAID), 2007). If neglected in the process of identifying ex-combatants, as highlighted in ( International Association for Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research, 2007), girls and women may be left out of the programmes designed to help ex combatants and consequently, ‘DDR activities run the risk of widening gender inequalities’.

It is at local and regional levels women are already brokering peace, but traditionally receive little recognition and support. Examples are the work done by women and women’s groups in South Sudan, Burundi, Northern Ireland and Columbia. The Mano River Women’s Peace Network (MARWOPNET) in West Africa (Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone), successfully brought the Heads of State of their three countries back to the negotiating table in 2001, and were a delegate, mediator and signatory to the Liberian peace talks in August 2003, ending a war which had started in 1989 (UN Women, 2015).

Having looked at some reasons why women should be involved in peacebuilding, this essay offers various suggestions to ensure their significant and meaningful participation.

What are the ways women can be brought to the table?

Women have used a range of methods to engage formally and informally in peace processes and many feminist groups continue to suggest wide-ranging means:

(i) At the Table:

- Involve women’s groups that are already active at the local and national level;

- Impose a female quota on the architects of the peacebuilding process to include women, but this does not always mean that the ‘women’s agenda’ will be included (Kaufman & Williams, 2018, p. 207) ;

- Get women to participate as part of negotiating delegations, whether representing women’s groups, a conflict party or some other constituent (O’Reilly, et al., 2015);

- Involve women at DDR stage – this is an essential stage as women have varied experiences of conflict (Kaufman & Williams, 2018, p. 206).

This direct participation does not always mean these groups have power over decisions made, and so if we broaden the concept of participation, we can ‘allow women to influence the negotiating parties through a more informal mechanism’ (O’Reilly, et al., 2015).

(ii) Around the Table:

- Observer status can be afforded to women who can also use this status to communicate to a broader forum, but the effectiveness of this status is dependent mainly on the primary mediator (O’Reilly, et al., 2015);

- Consultations with women’s groups, either formally or informally, can also be used effectively by the mediator and the leading peacebuilding group (O’Reilly, et al., 2015).

(iii) Build Capacity:

Rebuilding communities should be central to the objective of building sustainable peace, and therefore increasing the capacity and confidence of women in their communities should be key;

- Empower women through capacity building in terms of analytical skills, peacebuilding techniques, mediation, honing skills they may already be using at a local level (Devine, 2019);

- Enhance women’s participation in post-conflict elections through quotas;

- Provide funding on national and local levels, specifically for women’s groups with the aim of training women on how to conduct political campaigns both to influence and to partake;

- Create more space for women’s involvement in the justice system. Qualified women can be involved in the reconstruction of the justice and administration system by formulating laws that ensure gender quality and equal access to economic resources, e.g., land/property rights (Devine, 2019).

This essay argues that these ‘suggestions’ whilst worthwhile, are not addressing what were the underlying intentions and spirit of 1325, which is that, in order to build a peace which will endure for all constituents in a society, it is by including and recognising specific issues faced by, amongst other marginalised groups, women and girls. Fundamental concepts of, peace and conflict are too often understood from a male perspective; thus, this essay will make the case that a feminist perspective on these concepts is necessary to ensure a successful peacebuilding process which can bring us closer to the end goal of long-lasting peace.

A Feminist Perspective on Peace and Conflict Understanding Peace

The UN recognises that… ‘Peace is more than the end of armed conflict. Peace is a mode of behaviour. It is a deep-rooted commitment to the principles of liberty, justice, equality, and solidarity among all…’ (United Nations Security Council, 2014). This meaning of peace, as much more than the absence of armed conflict, is written into 1325, however many peacebuilding organisations consider peace as the temporary or long-term cessation of armed conflict and fail to acknowledge barriers to long-term peace.

In (Erzurum & Eren, 2014), they wrote of how Johan Galthung, widely considered the Father of peace studies, referred to the distinction between negative and positive peace. Negative peace being the absence of violent or armed conflict, and positive peace, the restoration of relationships, the rebuilding of societies, and the absence of indirect and structural violence. He called structural violence the physical impacts of economic, social, political and gender inequality. Galthung in (Galthung, 1969), stated that it is essential to pay attention not only to the impacts of military violence but also to the impact of this ‘structural violence’ on people. However, because it is mostly (though not exclusively) men who are combatants and they inform the traditional concept of peace, this has led to a focus by the international peacebuilding community on the cessation of armed conflict and achieving a negative peace. Achieving this negative peace does not necessarily lead to positive peace. So while we may achieve the former, if we are to achieve the latter sustainably, achieving a ‘Just Peace’ as envisaged by John Paul Lederach in (Lederach, 1999), the underlying structural violence in cultures, which may, and usually has, predated the violent conflict, should be examined and its impact on achieving a positive peace considered by peacebuilders.

In April 2016, UN Resolution 2282, defined sustaining peace as including ‘activities aimed at preventing the outbreak, escalation, continuation and recurrence of conflict, addressing root causes… and moving towards recovery, reconstruction and development’. This concept of sustainable peace and its link with positive peace, mirrors a feminist perspective on what peace looks like. Sanam Naraghi Anderlini in (Naraghi Anderlini, 2007), wrote that women see peace as ‘freedom from violence: access to safe housing, employment and education…[T]hey emphasise a holistic notion of peace, not just in military security and political terms but also in terms of human security…’. Thus, any peacebuilding process should include women, and acknowledge that their gendered experiences of conflict will affect their expectations for a peace which will last beyond that process.

Understanding conflict

Traditionally international actors in the area of peacebuilding have taken a narrow view of conflict, by defining it in mostly male, armed conflict terms or ‘a contested compatibility that concerns governments and/or territory …with the use of armed force’ ( International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2015). This view fails to recognise that personal security and insecurity are connected and central to the concept of conflict. Putting the individual at the centre of security issues, the concept of human security has increasingly been adopted by the UN in several important policy statements (Olonisakin, et al., 2011, p. 6). However, while welcome progress, this focus risks overlooking gender differences in what it means to be secure and in (McKay, 2004), Susan Mc Kay notes that, ‘Girls and women experience human insecurity differently from men and are subject to gender hierarchies and power inequities that exacerbate their insecurity’.

Although men make up most combatants and are more likely than women to die as a direct result from the conflict, women, on the other hand, are more likely to suffer and die from the indirect effects of the conflict. They are one of the most vulnerable groups during conflict for more reasons than just physical violence ( United States Agency for International Development (USAID), 2007, p. 8), and they constitute most of the large flow of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) associated with most conflicts. In addition, women in refugee and IDP camps face sexual exploitation and a lack of physical security, including rape and exposure to HIV/AIDS. They are also vulnerable to trafficking, and in many conflicts are treated as sexual weapons of war; used by armies to undermine the masculinity of the enemy.

Despite these examples of differing, gendered experiences of conflict, high-level peace-making and peacebuilding organisations and governments treat ‘conflict and ‘post-conflict’ settings separately (O’Reilly, et al., 2015); focussing efforts on the ending of combat and the consequent decline of in-combat mortality rate of mostly male combatants. However, for many women, their experiences of conflict and structural violence, neither begin nor end with the armed conflict. In fact, many women experience a ‘continuum of violence ‘, which is itself a form of structural violence. In (Cockburn, 2012), Cynthia Cockburn wrote that the expression ‘continuum of violence’ was originally devised to try and explain the concept that ‘when violence is our concern, episodes of armed conflict and periods called peace cannot and should not be considered entirely separate and different’. Additionally in conversation with Cynthia Enloe (Cockburn & Enloe, 2012), she spoke of this violence ‘…across different moments (peace-war-post-war), across different places (home-street-battlefield) and across different types of violence (sexual violence-gang fights-bombing raids)’ experienced by women.

Sanam Naraghi Anderlini in (Naraghi Anderlini, 2007, pp. 27-32) wrote of the early warning indicators of conflict in which authorities in the Balkans, for example, ignored a rise in domestic violence alongside the escalation of the conflict. Further evidence of this continuum is women’s experience of conflict during war, in which they are often used (as in Bosnia and Darfur for example), as sexual weapons of war through rape. This extreme form of violence is often used to bring shame to men who are meant to be their communities’ protectors and break the will of communities. UN agencies (UN Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary General, 2018) estimate that amongst several examples, in Rwanda during three months of genocide in 1994, between 100,000 and 250,000 women were raped; in Sierra Leone during the civil war 1991 – 2002, more than 60,000 women were raped; and in Liberia, from 1989-2003, more than 40,000 women suffered sexual violence. This violence against women continues post-conflict. Global estimates published by the World Health Organisation indicate that about 1 in 3 (35%) of women worldwide have experienced, either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime (World Health Organisation, 2017).

Taking a feminist perspective on peace, and with gendered experiences of conflict and structural violence, this essay will explore how these perspectives can inform a better understanding of peacebuilding.

A Feminist Perspective on Peacebuilding

The changing landscape of conflict has had an impact on how we address peacebuilding, as civil wars, rather than interstate wars, dominate the conflict landscape today (Paffenholz, et al., 2016). In today’s wars, strategies adopted by armed groups aim to bring the battle to a civilian population. This new battleground leads to a breakdown of the rule of law, security, and societal structures. With research showing that states relapse into civil wars within five years of a negotiated peace settlement in about 50% of cases (Westendorf, 2015), the security of civil society is critical in preventing further conflict. Consequently, the involvement of all constituents of civil society including women, in rebuilding society is essential. However, as reported in (O’Reilly, et al., 2015), traditionally peace processes are gendered processes, often reflecting gender inequities prevalent in many societies, and have focused on bringing the belligerents, who are rarely women, to the negotiating table. Bell and O’Rourke in (Ramsbotham, et al., 2016, p. 372) questioned the default membership of peace agreements where the ‘…elite (male) military and political powers who fought the conflict are also the main actors in negotiating the terms and structures of the peace process’. 1325 was intended in part to help counter this, but as evidenced above, getting women involved, is much more than having them at the table, it is by valuing their differing perspectives.

If international agents include marginalised populations of society in peacebuilding, such as women and girls, there is a better chance of addressing the underlying issues of gender imbalance and inequities. Oliver Richmond in (Ramsbotham, et al., 2016), suggested that if we apply a focus on achieving a ‘fusion of negative and positive peace,’ conflict resolution needs to be open to multiple methods and visions of peacebuilding’, and we should ‘…allow for the negotiation of a discursive practice of peace in which hegemony, domination, and oppression are identified and resolved’.

As has been examined in Section 2, men and women participate and experience conflict differently, and so the post-conflict period is also gendered. Laura Sjoberg in (Kaufman & Williams, 2018) wrote men and women ‘…participate both in conflict and in post-conflict transitions in ways that are constrained by the (gendered) social contexts in which they live.’ However merely including women in post conflict peace processes, will not mean that gender and its inequities have been integrated into any agreements. Many peacebuilding processes lack an understanding of women’s differing experiences before and during a conflict, leading to a peace agreement which may not be sustainable. As evidenced in Libya, the ceasefire agreed by UN mediators in December 2018, which did not invite women to participate, is precarious, and civil society is still badly affected by armed unrest. These Libyan women played a key role in the revolution of 2011 and have facilitated many of the informal processes for peace. A report from the International Peace Institute (International Peace Institute, 2018) says ‘[i]t will be impossible to build a legitimate and durable peace in Libya without addressing the demands for every security and justice illustrated by their [women’s] stories’.

Women’s contributions to informal peace efforts at a community level, as well as their varying experiences as combatants and victims, are often overlooked and so their exclusion in a post-conflict peacebuilding process begs the question; how do we define success? As indicated above in the case of Libya, the signing of a peace agreement, is only the beginning. It should not be an end in itself. If negative peace is the end goal of peacebuilding efforts, it is ignoring gender inequalities, and power imbalances often existing in civil society, which positive peace seeks to eliminate. Sustainable peace will only be achieved, in this essay’s view, if the goal is a fusion of negative and positive peace, and to have any hope of realising that goal, we must include women in peacebuilding processes, recognise their varying experiences, and address their pre-conflict experience of structural violence.

Conclusion

Despite the recognition in 1325 and subsequent Resolutions, that peace and security efforts are more sustainable when women are equal partners in the prevention of violent conflict and involved in peace processes, women are still underrepresented. This essay has argued women should be included, it has given reasons why, and it has looked at various examples of how this can happen. However, while one important aim of 1325 was to get ‘numbers’ of women into decision-making positions in peacebuilding organisations, this should not be the end goal.

Traditional peacebuilding processes often reflect the gendered power structures in existence before the conflict and seek a negative peace (the absence of armed conflict) while ignoring societal inequalities, thereby hampering the realisation of a positive peace. This essay maintains that achieving a negative peace, and not seeking a positive peace, is missing the opportunity to engender sustainable peace. The goal of peacebuilding should be to create a peace which endures. Thus, any agenda for peace should examine the structural violence and gender inequality women experience pre the conflict, and the root causes underlying this violence. The continuum of violence experienced by women, both public and private, is an important indicator of conflict within patriarchal societies, which privileges men and values masculinities more highly than femininities, and should not be ignored in any peacebuilding process.

The challenge for international agencies is to shift the paradigm on peacebuilding from pure cessation of armed conflict, to the pursuit of a positive, societal peace, which will last. A paradigm shift from engaging only with women when addressing gender inequality, to women and men; from the stereotyping of women as victims, to valuing them as agents of change; and from returning society, not to a limited peace of only a few, but to a ‘vision of a better peace, with the values of nonviolence, coexistence, and inclusivity at the centre’ (European Centre for Conflict Prevention, 2005). This paradigm shift challenges the very heart of 1325, moving from a quantitative focus on numbers of women around the table, to asking what our vision of peace is, and how we can make it sustainable.

Even if 1325 were numerically successful; in other words, if the quotas of women participating in peacebuilding processes were achieved, would this be enough? Would sustainable peace be realised? Reframing conflict and peace during peace processes and peacebuilding, to reflect women’s experiences and understanding, is necessary if sustainable peace is to become more than an aspiration. Without women at the heart of the process in terms of equity and proficiency, the dream and reality of peace will continue to remain elusive.

Bibliography

International Association for Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research, 2007. Empowerment: Women & Gender Issues: Women, Gender & Peacebuilding Processes. [Online] Available at: http://www.peacebuildinginitiative.org/index-2.html

[Accessed 15 May 2019].

International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2015. International IDEA. [Online] Available at: https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/women-in-conflict-and-peace.pdf[Accessed 25 April 2019].

United

States Agency for International Development (USAID), 2007. Women and

Conflict – An Introductory Guide for Programming. [Online]

Available at: http://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/douments/1865/toolkit_women_and_conflict_an

introductory_guide_for_programming.pdf

[Accessed 15 April 2019].

Bosetti, L. & Cooper, H., 2015. Where are the Women? How the UN is Falling Short on Gender and Conflict. [Online] Available at: http://cpr.unu.edu/where-are-the-women-how-the-un-is-falling-short-on-gender-and-conflict.html [Accessed 15 April 2019].

Cockburn, C., 2012. Anti-Militarism, Political and Gender Dynamics of Peace Movements. 1st ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cockburn, C. & Enloe, C., 2012. Militarism, Patriarchy and Peace Movements: Cynthia Cockburn and Cynthia Enloe in conversation. International Feminist Journal of Politics, December, 14(4), pp. 550-557.

Devine, P., 2019. Shalom Centre for Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation. [Online] Available at: https://shalomconflictcenter.org/

[Accessed May 2019].

Erzurum, K. & Eren, B., 2014. Women in Peacebuilding: A Criticism of Gendered Solutions in Postconflict Situations. Journal of Applied Securtiy Research, 9(2), pp. 236-256.

European Centre for Conflict Prevention, 2005. The Role of Women in Peacekeeping. [Online] Available at: http/www.conflictrecovery.org

[Accessed 25 April 2019].

Galthung, J., 1969. Violence, Peace, and Peace Research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), pp. 167-191.

International Peace Institute, 2018. Libya Talks Embody Missing Participation of Women in Peace Processes. [Online] Available at: http://theglobalobservatory.org/2018/12/libya-talks-embody-missing-participation-women-peace-processses

[Accessed 10 May 2019].

Kaufman, J. P. & Williams, K. P., 2018. Women, Gender Equality, and Post Conflict Transformation – Lessons Learned, Implications for the future. London and New York: Routledge (Taylor&Francis Group).

Lederach, J. P., 1999. Justpeace-the Challenge of the 21st Century. In: People Building Peace, 35 Inspiring Stories from Around the World. Utrecht: European Centre for Conflict Prevention , pp. 27-36.

McKay, S., 2004. Chapter 7 , Women, Human Security, and Peace-Building: A Feminist Analysis. Conflict and Human Security: A Search for New Approaches of Peace-Building, Issue 19.

Naraghi Anderlini, S., 2007. Women Building Peace- What they do, Why it matters. Boulder(Colorado): Lynne Rienner.

Naraghi Anderlini, S. & Tirman, J., 2010. What the Women Say, Paticipation & UNSCR 1325 – A Case Study Assessment, s.l.: International Civil Society Action Network and the MIT Center for International Studies.

O’Flynn, I. & Russell, D., 2011. Should Peace Agreements Recognise Women?. Ethnopolitics, 3 March, 10(1), pp. 35-50.

Olonisakin, F., Barnes, K. & Ikpe, E. eds., 2011. Women, Peace and Security: Translating Policy into Practice. New York(New York): Routledge (Taylor&Francis Group).

O’Reilly, M., O’Suilleabhain & Paffenholz, T., 2015. Reimagining Peacemaking: Womens Roles in Peace Processes, New York: IPI Publications International Peace Institute.

Paffenholz, T. et al., 2016. “Making Women Count – Not Just Counting Women: Asessing Womens inclusion and Influence on Peace Negotiations”, Geneva:: Inclusive Peace and Transition Initiative (The Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies) and UN Women.

Pinker, S., 2012. The Better Angels of our Nature. 1st ed. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Ramsbotham, O., Woodhouse, T. & Miall, H., 2016. Contemporary Conflict Resolution; The prevention, management, and transformation of deadly conflicts. 4th ed. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Shekhawat, S., ed., 2018. Gender, Conflict, Peace, And UNSC Resolution 1325. Maryland: Lexington Books.

UN Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary General, 2018. Conflict Related Sexual Violence – Report of the Secretary General. [Online]

Available at: https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/digital-library/reports/ [Accessed 15 May 2019].

UN Women,

2015. Preventing Conflict, Transforming Justice, Securing the Peace. A

Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council

resolution 1325. [Online]

Available at: http://www.reliefweb.int/report/world/preventing-conflict-transforming-justice-securing-peace-global-study-implementation

[Accessed 1 May 2019].

United Nations Security Council, 2000. Security Council Resolutions 2000. [Online] Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N00/720/18/PDF/N0072018.pdf?OpenElement

[Accessed 3 May 2019].

United Nations Security Council, 2014. Secretary General Remarks to High Level Forum on the Culture of Peace. [Online] Available at: http://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2014-09-09/secretary-generals-remarks-high-level-forum-culture-peace

[Accessed 10 May 2019].

Westendorf, J.-K., 2015. Why Peace Processes Fail – Negotiating Insecurity After Civil War. Boulder(Colorado): Lynne Rienner Publisher.

World Health Organisation, 2017. [Online]

Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women [Accessed 1 May 2019].