Focus: Conflict Transformation and Peace-Building under-pinning Development and the

Role of Civil Society Organisations

Context: 1. UN Sustainable Peace Initiative, 2016

2. Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict –

World Bank and the UN, 2018

3. SDG No. 16 focused specifically on Peace

Introduction

The UN Sustainable Peace Initiative places preventive action and post-conflict peace-building on par with peace-making and peace-keeping. The report by the Secretary-General to the HLM on Sustaining Peace in April has laid the groundwork for an important policy-breakthrough, empowering civilians with new tools, better management practices, and hopefully new financial resources to contribute to a more integrated and coherent framework for global conflict management that delivers positive peace.

Important features of the initiative are:

- It elevates the role of civil society and regional organisations in sustaining peace.

- It stresses that the UN development system and development practitioners in general are central to conflict prevention and sustaining peace.

- It buttresses the case for “more predictable and sustained financing” for civilian-led peace-building through a proposed Funding Compact with Member States, against the backdrop of declining development assistance to conflict-affected countries as a share of global aid (from 40% in 2005 to 28% in 2015).

Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict is a joint study by the UN and the World Bank. The study originates from the conviction on the part of both institutions that the attention of the international community needs to be urgently refocused on prevention of conflict.

The human and economic cost of conflicts around the world requires all concerned to work more collaboratively. The SDGs should be at the core of this approach. Development actors need to provide more support to national and regional prevention agendas through targeted, flexible, and sustained engagement. Prevention agendas, in turn, should be integrated into development policies and efforts, because prevention is cost-effective, saves lives, and safeguards development gains.

Inclusive decision making is fundamental to sustaining peace at all levels, as are long-term policies to address economic, social, and political aspirations. Fostering the participation of young people as well as of the organizations, movements, and networks that represent them is crucial. Women’s meaningful participation in all aspects of peace and security is critical to effectiveness, including in peace processes, where it has been shown to have a direct impact on the sustainability of agreements reached.

The SDGs in the Context of Peace

SDG No. 16 aims to promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide justice for all, and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels. It asks “how can a country develop—how can people eat and teach and learn and work and raise families—without peace? And how can a country have peace without justice, without human rights, without government based on the rule of law?

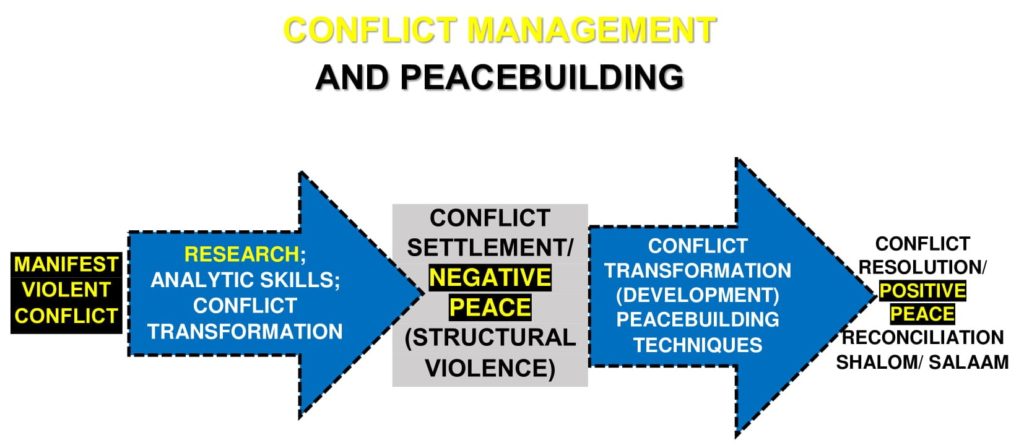

That goal is specifically focused on positive peace in societies where sustainable development can take place and be effective. All of the SDGs are predicated on a minimum of negative peace and the potential for the realization of positive peace (concept of negative vs positive peace explained later in this submission). They recognise that sustainable development without sustainable peace is not possible.

Ireland’s Overseas Aid Policy

Ireland’s overseas aid programme should be well informed by evidential research on the geopolitical context of its appropriation at the grassroots, national, regional and global dimensions.

From the standpoint of a peace-development nexus where issues of security, equality, equity, justice, and world/planet sustainability are inherent, it is self-evident that in conflict environments where people are killed, maimed and displaced persistently, essential social values such as peace, truth, justice and mercy cannot take deep communal root. These values are of utmost importance for people to live normal lives aspiring to the fullness of sustainable peace.

This type of peace is theoretically understood as positive peace as distinct from negative peace. Positive peace exists when and where all sides are mutually committed to a coexistence of interdependence expressed in ensuring the security, development and harmonious wellbeing of each other. However, in the afore mentioned context of manifest violent conflict, people at best only experience intermittent time-spans of negative peace which is merely the absence of physical violence.

Of equal significance concerning the same conflict environments is the fact that communities cannot experience sustained development because periodically schools, hospitals, clinics, community facilities and other infrastructure become inoperable or totally destroyed. In line with the ‘Brundtland’ philosophy, sustainable development is oriented to meeting the needs of the present generations without compromising the ability of future one’s to meet their needs.

We will be forever rebuilding/rehabilitating development institutions, and be ethically indebted, if not legally obliged, to provide humanitarian interventions and humanitarian aid insertions if we do not address the root causes of conflict. Comprehensive knowledge of the peace-development nexus (security may be added into the equation) at an academic and practitioner level is imperative in policy making and implementation. This knowledge is essential for if more equal, peaceful and sustainable world is to emerge. Security, understood as human security, which is inextricably linked to environmental security, is an integral component within the dynamics of the nexus. Within this framework the variables of core resources for survival, the political-economy of governance and infrastructure security largely determine the traction dynamics in the peace-development interplay.

Underdevelopment and conflict cannot be separated from issues of infrastructure because of its role in governance and the institutions to provide human security in all its dimensions. Thus, the component factor of infrastructure-insecurity has to be addressed in any policy intending to generate a more equal, peaceful sustainable world. Insecurity, like security, stands on a long continuum and therefore cannot be understood in absolute terms. Insecurity, like security, is a subjective state in which an individual or a collective group does not feel free of threats, anxiety and/or danger. Such insecurities have typically been defined in relation to nation-states regarding border or institutions responsible for governance.

In today’s globalised geopolitical context the origins of threats, whether military, political or economic, may arise internally or externally to a country. The responsibility for the formulation and implementation of policy and strategy designed to counter insecurity threats is not exclusive to any one government organisation, nor ever independent of the state impacted. The nation-state is not the sole entity to be protected against insecurity threats.

Anxiety and related trauma are key aspects of insecurity. Anxiety is an emotion and state of mind impacting on the security of individuals or groups in society characterized by aversive, cognitive and behavioural components. It is a normal inborn response either to threat – to one’s person, attitudes, or self -esteem – or the absence of people or objects that assure and signify safety. Anxiety, as a phenomenon, is undoubtedly psychological, frequently, entailing hyper vigilance, avoidance and paralysis of action, but its data sources are not. Anxiety can thus be assessed other than not psychological because its data sources are predominantly social and economic.

In peace-development policy and operations, the issue of security needs to focus much more on individual and human rights within the State environmental security framework rather than on the State security per se. Human security was broadly defined by the (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) as “safety from such chronic threats as hunger, disease and repression” and also protection from sudden and hurtful disruptions in the patterns of daily life (UNDP, 1994).

Human security has four distinctive aspects: a) political security, defined as the freedom from dictatorship and other arbitrary governments … political security policy should involve looking at patterns of democratic governance, the presence of gross structural violence and respect for human rights; b) economic and social security, defined as the freedom from poverty and want; c) cultural security, defined as freedom from ethnic and religious dominance; d). environmental security, defined as the freedom from environmental destruction and resource scarcity.

A state has prime responsibility for policy and structured conflict management strategies to ensure human security for everyone equally. Providing basic human needs and the possibilities to actualize one’s potential are measuring rods underpinning policy on the peace-development-security nexus. In societies which do not have manifest violence but are in a constant state of negative peace evidenced in poor governance, development interventions are central to achieving a more equal (equitable/just/free) peaceful (negative or positive) and sustainable world. Structural violence is often the underlying causes of manifest conflict.

In Africa intra-state conflict is a persistent phenomenon with contagion consequences straggling borders. Few states are exempt from critical systemic stressful factors relating to multi-ethnic composition, manifest and structural conflicts, governance violence, development limitations, gender inequity, democratic stability etc. The goal of achieving a more equal, peaceful sustainable world cannot ignore factors of political economy, infrastructure insecurity and core resources. There is an inseparable link between environmental resources and human security. Environmental security is principally about the freedom from environmental destruction and resource scarcity.

Conflict can rarely be disentangled from variables associated with the carrying capacity of the environment and human security. The acute linkage between environmental degradation and climate change effects is having detrimental impact on the supply of core resources to meet basic human needs and actualize potential. At the same time the fast evolving population growth is having alarming demand consequences to attain the same resources. Cross-cutting these conflict escalating variables of demand and supply is the volatile fluctuation of structural violence evidenced through the blatant inequitable disparity in the distribution and governance of resources, be they tangible or intangible. This demand-supply-inequity correlation needs constant attention within any policy advocating a more equal, peaceful, sustainable world where development interventions are fully effective.

Democratic modes of governance incorporate various forms of fundamental perspectives which do not advocate violence within society. However, when fundamental viewpoints become fundamentalism or negatively radicalized towards intolerance, the toxicity of extremism emerges with detrimental implications for human security, equality, peace and development. To achieve a sustainable world within a peace-development framework the pervasive phenomenon of religious ideological extremism demands response. Ireland’s

overseas aid policy needs to give urgent attention to the stages, dynamics and drivers of this extremism.

When religion becomes disproportionately energised by increasing quantitative institutional membership, to the detriment of qualitative spiritual transformation, the potential for it becoming a destructive factor in conflict generation escalates. The propagation of religions as mere institutions becomes the primary focus rather than their core spiritual message with respect to peace, truth, justice and mercy. The religionization of politics and the politicization of religion have brutal negative implications on the process-deterioration of tolerance to intolerance. It entails negative radicalised fundamentalism deteriorating to non-violent extremism whereby proponents of alternative viewpoints try to prohibit freedom of expression.

Further degenerative processes lead to manifest violent extremism, operationalized in terrorism. The terroristic acts of this ‘extremism’ are oriented towards eradicating alternative modes of perception and existence. It negatively impacts on governance oriented to a sustainable world epitomised by peaceful interdependence coexistence. The spread of religious ideological extremism, underpinned by socio-eco-political-religious radicalisation dynamics and drivers, is the basis of peace-development policies to advocate for relevant capacity and resources.

While conflict management, development, humanitarian intervention and humanitarian aid are interrelated, the strategic transformation of the underlying causes of manifest conflict to situations and positive peace must be the prime guiding principle of Ireland’s overseas aid programme. The continuum stages from manifest conflict to positive peace must be well understood as outlined in the following simplified graph.

Development policy and its modus-operando of intervention should be systematic, evidence-based, selective and focused on priority goals. The equal empowerment of all people to meet basic human needs, actualize their potential and increase shared prosperity in a sustainable manner are the priority. Specificity is a requirement of the scientific way of knowing about the external world and improving its operational dynamics towards an agreed vision and sustainability.

From the sustainable peace-development, clarity about what is signified by the concepts of equality, peace, development and sustainable world is important. One group may understand a concept such as equality in terms of ethical and legal rights; another in terms of equity in distribution of resources; others may focus on respecting cultural/religious differences concerning human and gender right’s interpretation etc. The specificity is imperative for clarity on the end vision of conflict management as it transforms the underlying causes of conflict, poverty, underdevelopment inequality etc. This vision is fundamentally different from the goals applicable in responding to conflict’s symptoms in the form of humanitarian intervention and humanitarian aid.

Holistic conflict transformation interventions necessitate the empowerment of local communities to be the prime architects of their own future. In this regard, policy needs to address the bringing together of the key influential opinion-shapers, for example, chiefs, elders, women and religious leaders, youth representatives, teachers, warriors, political economic-actors etc., into the process. These actors have to own the process through dialogue-praxis (Dia-Praxis). Applying outside expertise without appropriate insertion and engagement with the local communities impacted by conflict and underdevelopment is a volatile strategy unlikely of achieving sustainable peace-development.

Ireland’s overseas aid policy should never settle for mere negative peace, a type of peace evident in the political economy of security and social cohesion in Northern Ireland, and many underdeveloped countries where the absence of conflict is only ensured by fear of the State repressive apparatuses – army and police. For positive peace to emerge the State’s ideological apparatus, (educational systems, media, religious benevolence, constitutional ideals of human rights, inspirational policies on peace-development interventions, with global humane dimensions, etc.,) has to be dominant and unyielding.

The empowerment of the local people with conflict management aptitudes requires highly qualified teams of non-sectarian, gender sensitive, peace and development practitioners. A committed long-term insertion in the conflict zone will be necessary in this accompaniment. Policy needs to emphasise that specialisation in research, peace studies, development, project management, political science, international relations, comparative religions etc are essential for sustainable development to materialize.The mind-set of partnership based on genuine equality is indispensable to this process avoiding any indication of a condescending armchair donor mentality of command and control.

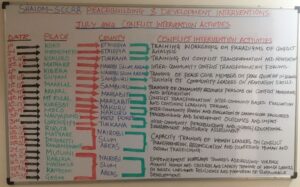

The following peace-development model is a proposal to Ireland’s overseas aid policy to be reflected in interventions in conflict environments, be they manifest or structural. The model has been designed and implemented by the Shalom Center for Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation (SCCRR), addressing rural and urban conflicts in Eastern Africa over the past nine years. The conflict environments are impoverished and underdeveloped, characterised by persistent structural and manifest violence. These situations challenge the progression to a sustainable world where issues of equality, human and gender rights, among others, are legitimized in law and culture practice.

- Conduct quantitative and qualitative empirical research into the underlying causes of conflict to inform conflict transformation/development policy and interventions;

- Empower local community leaders with analytical skills, conflict transformation processes, peace-building techniques, as a forerunner to problem-solving workshops where interdependent reconciliation rudiments and joint action plans for development are activated ;

- Influence local, national and regional institutional peace and development policies/structures addressing factors of conflict management, human insecurity, underdevelopment;

- Strengthen the role of religious organisations, civic organisations, and NGOs in peace and development theory and practitioner proficiencies;

- Develop inter-ethnic/inter-religious institutions of conflict management and social development, particularly prioritise education through the design and promotion of peace education syllabus in adequately equipped institutes.

In 2018, Misean Cara – an agent of Irish Aid – carried out an effectiveness review of Shalom-SCCRR’s methodology which is based on above model. The highest possible rating was awarded, stating:

“In many aspects, Shalom-SCCRR’s contextually driven, rigorous but adaptable and forward-looking methodology represents a model approach towards peace-building in highly complex situations, such as those that pertain in Northern Kenya. Grounding the project interventions on local research is crucial to its success, and the emphasis on education (and peace education in particular) is vital in forming and influencing the mindsets of the next generation, in what is inevitably a long-term change process towards peaceful co-existence of a wide range of warring parties. The approach, with its emphasis on community leadership, stakeholder participation, high technical competency, logic models, and results frameworks, stories of change and advocacy linkages also reflects current best practice within both the peacebuilding and development sectors”.

Any policy addressing issues of peace and development, or conflict and under-development should be comprehensive in terms of the paradigms applied and the multiple theories emanating from them. This is essential for the academic research and the training of the key influential opinion shapers with the analytical skills to identify underlying, proximate and trigger causes of conflict and underdevelopment. These are absolute for the realization of a progressive conflict transformation and peace-building.

The three main paradigms which dominate the disciplines of peace studies and political science are:

- Strategist-Realism, which concentrates on the role of power as the dominant variable in achieving one’s security and interests. Zero-sum dynamics of power over the weaker party is operationalized through manipulative control, threats, sanctions and coercion. A win-win mentality is not prioritized in the interactive relationship of the parties involved. It is the dominant paradigm pervading social interaction in world politics at the regional, interstate and intra-state levels. (Hans Morganthau).

- The peace research paradigm focuses on the role of social structures-institutions inhibiting the actualization of people’s potential, as the basis for conflict in society. Johan Galtung is considered the expert of this paradigm; ‘Structural violence is present when human beings are influenced so that their somatic and mental realizations are below their potential realizations’, (Johan Galtung, 1969). The structures have to be rejected, transformed and/or new ones put in place if there is to be sustainable peace and development in a world where equality and equity prevail.

- The conceptual basis of the conflict research paradigm is anchored in the world society school of international relations. John Burton is a founder and champion of this school of thought. It claims the imperative to war does not arise from the nature of State or its external relations but from the way the environment acts on individuals in their interactions and inter-relationships. Conflict is not considered instinctual or that people need to dominate other mankind; the values which satisfy human and ontological needs are not in short supply. .

A foremost scholar to date in comparatively studying these paradigms is A.J. R Groom who maintains;

“Conflict, its causes, modalities, outcomes and effects is a matter central to these three approaches which characterize for the most part the study and practice of international relations in the English speaking world today. What we think causes conflict determines what we think we can do about it. And both are a reflection of our conceptual framework for studying world society. It matters too, if we are to survive.”

This perspective underpins policy making in literature on issues of conflict, poverty, and underdevelopment in our world today. This is very evident in UN/EU literature. Scholarly analysis from intellectuals and practitioners in these disciplines is increasing as is the establishment of relevant educational institutions, for example, in the USA, Ireland and Kenya.

In the highly commended books, Leashing the Dogs of War: Conflict Management in a Divided World (2008), and Managing Conflict in a World Adrift, (2015), over 60 of the world’s leading international affairs analysts examined the relationship between political, social or economic change and the outbreak and spread of structural and manifest conflict. The conflict management policy implications for attending to matters of human rights, environmental security and sustainable development runs through the narratives.

Having attended to issues of research and analytical skills, the next task for policy is to focus on the equipping of all stakeholders with conflict transformation skills and peace-building techniques. This should be done in conjunction with having policy guidelines on the availability of appropriate sustainable development capacity/resources. These two aspects are necessary for achieving positive peace, and for counteracting a regress to negative peace and manifest violence.

This process is predicated on conflict transformation addressing four key areas which needing intense scrutiny of;

Personal: The psychological, spiritual, emotional implications on conflict and peace.

Relational: The behavioural, stereotyping, communication between parties

Structural: Institutional weaknesses which need urgent remedial and development interventions to counteract their impact on structural and manifest violence interrogated vis-à-vis negative impacts on the actualization of peoples/community’s somatic and mental potentials.

Cultural: Conflict sanctioned by culture, such as traditional violent customs, negative ethnicity/ethnocentrism.

As all parties in conflict need training in this process of transformation, policy guidelines are critical. In sync with this, policy needs to be the signpost for sustainable development interventions constantly impelling the peace progression. To finally reach conflict resolution/reconciliation attention, there is a need to bring all sides in to the process of Problem Solving Workshops in order for reconciliation to solidify.

Reconciliation is bed-rocked ultimately on negative peace first emerging which in turn is processed towards positive peace through attending to issues of: a) ‘Truth’ in its actuality and perception; b) ‘Justice’ in the examination of injustices committed needing attention, and finally the openness by all parties to the operationalism of ‘Mercy’, perpetually applied and experienced at inter-communal levels. Without this understanding being operative in a holistic process of ‘Dialogue-Praxis’ (dia-praxis), there is a perilous danger of it being sabotaged, and retrogressing to negative peace followed by the re-emergence of manifest violent conflict. The present Northern Ireland conflict management context helps to understand this dynamic and the dangers attached to deficient policy.

Development project interventions are practically impossible in the period between manifest violent conflict and attaining a cease-fire (an attribute of negative peace). However there is almost an absolute need for such development interventions, be they in education, health, livelihoods, medicine, peace institutions etc., on the road map between negative and positive peace.

It is in the problem solving workshop forums that institutional arrangements and action plans for a shared future of interdependent co-existence becomes reality. Inter-communal/inter-religious education, development of trade and infrastructural projects impacting on basic human needs and communal actualization of potential should be encouraged in any sustainable peace building policy. Policy making addressing peace processes cannot underestimate the importance of acquaintance with conflict environment/actors as well as ensuring the provision of appropriate peacebuilding professionals. Correspondingly, these are vital components for consideration prior to the initiation of development interventions. The perspective that, theory without practice is empty and practice without theory is blind, is so relevant; flawed theoretical foundations provide dissatisfactory results and poor value for process investment.

The taming of the limitations within each paradigm in respect to its understanding of the causes of conflict and its management requires unbounded attention also. A prudent policy on peace and development needs to translate into appropriate and intensive interventions as distinct from just band-aid symptom treatment. Admittedly, the symptom treatment does have value for those affected but has minimal preventative impact in counteracting the underlying causes of persistent protractible conflicts. A policy should counter continually pouring money through a sieve if it fails to be preventative in essence. A good truism in this regard is, ‘if we continue to do what we have always done we should not be surprised if we get what we always got’.

The Shalom-SCCRR model outlined here is endorsed by high profile peace and development policy makers and practitioners. The model has also attracted the attention of the Irish government, World Bank, and the UN resulting in recommendation for UN accreditation. In addition to the Misean Cara commissioned effectiveness review mentioned earlier, the Trocaire Kenya Country Director after a Trocaire evaluation of Shalom-SCCRR model stated: “I note some core components of Shalom-SCCRR’s structure and approach that adds significant value

- The modular methodology that Shalom-SCCRR adopts allows communities in traditional violent hotspots to build their skills in peace building and conflict resolution in a manner that is accessible and adaptable to the local context. Learning builds on existing knowledge and is embedded in a manner that is sustainable and transformative.

- The analytical, diplomatic and facilitative skills of Shalom-SCCRR staff as well as their high levels of education and peacebuilding techniques has ensured that entry into communities and situations of extreme tension has been welcomed and appreciated.

- The inclusion of key stakeholders in the process ensures that all actors have a common understanding of and commitment to the peacebuilding or the ‘Shalom-SCCRR’ process. This builds consensus and eases tension between the various actors such that community elders, women, youth, local government, the police and clergy can all hold each other to account.

- Trocaire acknowledges and values the integrated nature of Shalom-SCCRR’s approach to peace-building. In particular, we appreciate the inclusion of and support for inter-ethnic schools where a young and vibrant generation is being exposed to new possibilities and a future full of hope and peaceful coexistence.

- I also visited the Kibera slum this year and was impressed by the capacity and knowledge that local women have gained through your work. They were able to articulate the issues, interact and resolve conflict in a manner that would not have been previously possible. An unintended but welcome consequence of this is that women’s voice and negotiation in their own homes has significantly increased.

- Your ground work and research before entry into communities is something I wish others would learn from and I am particularly impressed by the research methodology applied before any plan of action is put in place”.

May I take this opportunity of thanking you and your team for such dedication and professionalism. We rely on Shalom-SCCRR to help us avert deep division in the communities that we serve and wish you continued success in your work”.

In March 2018, Nasser Ega-Musa, Director of UNIC Nairobi, who are well acquainted with Shalom-SCCRR methodology, Track I and II partners etc., when recommending Shalom-SCCRR to UNDPI in New York, expressed “confidence that Shalom-SCCRR will be a great asset and add value to the United Nations’ work”

The Irish Minister for Overseas Development, Joe McHugh TD, at a Council of Minister’s Meeting in Brussels in May 2017 when discussing issues of sustainable peace and development stated: “This was an opportunity for us as a country to give our ongoing commitment to many of the crisis that there are, especially in the Horn of Africa … but on top of that we were focused on our sustainable development goals. We are very focused on – in line with António Guterres as well – at how we can look at and examine the root causes; looking at peace and reconciliation; to looking at how we can bring peace which will obviously lead to sustainable development. We can’t have sustainable development without peace. And I also pointed to the great work that is being done in Northern Kenya by a group called Shalom-SCCRR – interethnic conflict reconciliation – where for the first time in a particular region, even with drought and massive challenges, peace is holding. So we have to look at the solutions. My message today from Ireland to Europe was – if there are examples that are working we should look at them, we should support them, and we should also look at our own experience”. https://shalomconflictcenter.org/eu-development-council-we-cant-have-sustainable-development-without-peace/.

Shalom-SCCRR’s model and methodology has led to many partnerships such as:

- For the past 6 years a MoU exists with IGAD (the Inter-Governmental Authority for Development in the Horn of Africa – eight countries). This is facilitating ongoing collaborative interventions on policies and practices concerning the peace-development – security nexus.

- Shalom-SCCRR has MoUs with the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for Conflict Intervention at Maynooth University, with the George Mitchell Institute for Conflict Transformation at Queen’s University Belfast, and with the Association of Member Episcopal Conferences in Eastern Africa – eight countries.

Additionally, the Shalom-SCCRR approach has attracted high profile attention in the USA – see https://shalomconflictcenter.org/fr-patrick-devine-to-speak-at-irish-embassy-in-washington/ as well as invited lectures at the Harvard School of Law to their Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program, https://shalomconflictcenter.org/harvard-lecture-focuses-on-model-for-peace/ and to the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Texas, Austin, among others.

- Fergal Keane, BBC Africa Editor, writing about Shalom-SCCRR’s work in the Irish Independent said: “Kenya needs them in its slums and beleaguered western villages where tension is rising by the day. What they do here matters to all of Africa…” https://shalomconflictcenter.org/bbc-and-shalom-sccrr-confer/

- The World Bank has engaged in numerous meetings with Shalom-SCCRR concerning its methodology and model: https://shalomconflictcenter.org/world-bank-confers-with-shalom-on-peacebuilding-methodology-and-research/

Conclusion

We believe that Ireland’s overseas aid policy should prioritise conflict transformation and peace-building that involves the participation of civil society organisations with the appropriate competence and capacity, and that this should be reflected in a meaningful manner it its new strategy.

Fr. Patrick Devine, Ph.D, SMA

(Ph.D; Political Science and Public Administration, MA; Peace Studies and International Relations)

Chairman

Shalom Center of Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation (SCCRR)

11 August 2018

One Comment