By: Ms. Paula Soumaya Domit MA, & Rev. Dr. Patrick. R. Devine (Briefing Paper No. 13).

(Peer reviewed by the Shalom-SCCRR Department of Research).

(Shalom-SCCRR’s implementation of its Educational Module on the Prevention and Response to Human and Organ Trafficking is operationalized at the ‘Shalom Empowerment Center addressing Violence against Women and Children’(SEC) and in over 30 conflict environments in eastern Africa where it is consistently intervening to transform Interethnic Conflict and Religious Ideological Extremism, (https://shalomconflictcenter.org/a-perspective-on-the-philosophy-and-work-of-shalom-sccrr-by-prof-wanakayi-k-omoka-rip-remembered-with-the-2023-results-added-by-the-dept-of-monitoring-evaluation-and-learning-mel/).

HUMAN AND ORGAN TRAFFICKING: WHY SHALOM-SCCRR INTERVENES AND RESPONDS!

The Shalom Center for Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation (SCCRR) is a non-sectarian inter-religious conflict transformation and peacebuilding non-governmental organization founded in Africa. Its vision is a society where peace, justice, and reconciliation prevail throughout the continent (https://shalomconflictcenter.org/ ). Its main objective is to attain conflict resolution for all people in Africa through empowering local communities engaged in inter-ethnic conflict, religious ideological extremism, and violence against women and children to be the architects of their own interdependent future of reconciled coexistence (https://shalomconflictcenter.org/shalom-sccrrs-conflict-transformation-and-peacebuilding-intervention-methodology-and-processes-synopsis/). Human rights and positive peace are mutually reinforcing. Recognizing this relationship, Shalom-SCCRR’s programs of intervention maximize addressing human rights. SCCRR has been actively funding work aimed at overcoming ‘human trafficking’ for over a decade in Eastern Africa (https://shalomconflictcenter.org/chairmans-report-for-2017/).

Across East Africa, but particularly acutely in the slums of Nairobi, human trafficking is a pervasive hindrance to peace, both negative and positive peace. Human trafficking is a violation of the rights and freedoms of the human person (https://shalomconflictcenter.org/human-rights-are-a-foundation-of-shalom-sccrrs-conflict-resolution-and-reconciliation-interventions-2/).

It infringes on the right to life, the right to liberty and security, the right not to be submitted to slavery, servitude, forced labour or bonded labour, and the right to freedom of movement, among others (https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/). These rights are enshrined within numerous international human rights treaties, condemning human trafficking in all its forms.

According to the U.S. Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report 2020, the government of Kenya reported identifying 853 victims of trafficking – 275 adult females, 351 girls, and 227 boys – a significant increase compared with about 400 identified victims in 2018. Most cases of human trafficking go unreported, so the real number of victims may be orders of magnitude larger. Most victims are unaccounted for in these figures (https://www.indcatholicnews.com/news/45158).

Trafficked women and girls encounter high rates of physical and sexual violence, including homicide and torture, psychological abuse, horrific work and living conditions, and extreme deprivation while in transit. Serious mental health problems result from trafficking, including anxiety, depression, self-injurious behaviour, suicidal ideation and suicide, drug and alcohol addiction, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dissociative disorders and complex PTSD (https://shalomconflictcenter.org/shalom-sccrrs-interventions-towards-healing-post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd-among-victims-of-conflict-in-eastern-africa%ef%bf%bc/).

Human rights have a symbiotic relationship with conflict transformation, peacebuilding, and reducing violence against women and children. The protection of human rights, and thereby the prevention of human trafficking, plays a critical part in building sustainable, positive peace. Without adequate protection of the human person’s dignity and rights, peace cannot flourish. Respecting and promoting human dignity and rights is not only a moral imperative but also a practical approach to building and maintaining a peaceful society. The core principles of human rights, according to Dorfman (2010), “hold up the vision of a free, just, and peaceful world and set minimum standards for how individuals and institutions everywhere should treat people.”

Shalom-SCCRR works closely with community leaders (influential opinion shapers) in the urban informal settlements of Nairobi, training them with analytical skills in conflict analysis and transformation techniques (https://shalomconflictcenter.org/briefing-paper-no-1/). With this information, they can be peacebuilders in their community (https://shalomconflictcenter.org/eastern-africa-shalom-empowerment-center-sec-addressing-violence-against-women-and-children-concept-document/). Shalom-trained community members, among others, in human trafficking hot spots, such as the urban informal settlements, are best situated to participate in the work to combat this phenomenon. Using Shalom’s existing strategy, it can empower these community leaders with information about human trafficking, its prevalence in the community, strategies for prevention and attending to its violent reverberations. Raising awareness and reducing incidences of human and organ-trafficking is critical to conflict transformation and peacebuilding processes.

WHAT IS HUMAN TRAFFICKING?

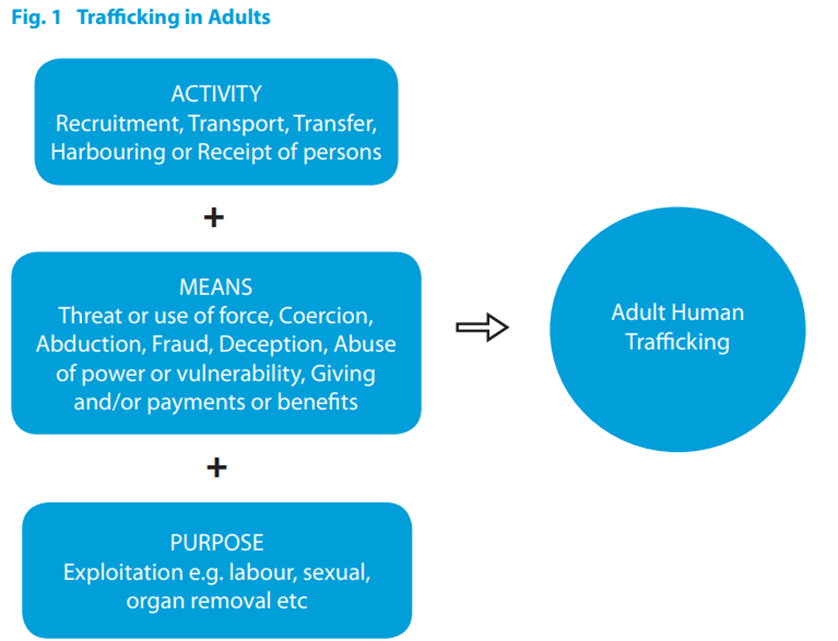

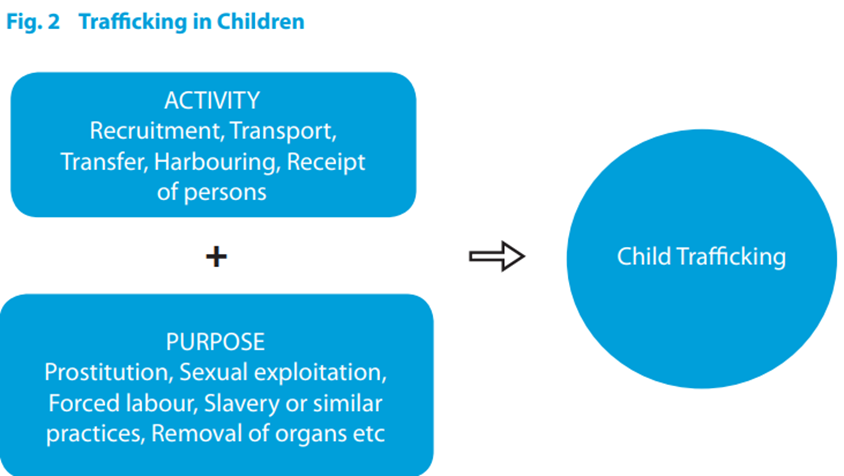

- Trafficking in persons is defined as the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation, (see; https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/Toolkit-files/08-58296_tool_1-1.pdf )Exploitation may include forced labour, slavery, prostitution, sexual exploitation, or similar practices, removal of organs.

- See Appendix Figures 1 & 2 for charts defining victims of trafficking.

- Trafficking in the slums of Nairobi follows similar patterns, including fraudulent job offers or offers for schooling, taking of lost children, buying/selling/kidnapping of babies, forced prostitution of children and young women, and forced labour.

WHO IS AFFECTED IN THE COMMUNITY?

- Men, women, and children can all be victims, but the targeting of women, children, and migrants is prevalent. Most of the trafficking focuses on labour and sexual exploitation.

- Nairobi is a popular destination of trafficking – both as a recruitment point and an exploitation point in Eastern Africa.

- Exploitation in Nairobi:

- Popular routes: “corridor towards Southern Africa. Ethiopian and other irregular migrants typically cross the border into Kenya near Moyale, then travel to Marsabit, Isiolo or Nanyuki before arriving in Nairobi.” (IOM)

- Trucks transporting goods from Kenya to Somalia have also returned to Kenya with girls and women subsequently exploited in brothels in Nairobi or Mombasa (IOM)

- Overwhelming majority of victims are sourced from rural areas or other African countries. Other sources include institutions like schools, churches, children’s homes and refugee camps. Road transport is the most common form of transportation for trafficking. (National Crime Research Center)

- Recruitment in Nairobi:

- In most cases, recruiters are people who are known to the victim or their family or who can create a sense of trust. Recruiters are often friends, family, community members, business people (perceived as successful), and job agents.

- “Deception (false promises, enticements, handouts) featured as the commonly used method of recruitment, scoring 53.4%. Others were abductions, media, kidnappings and referrals by relatives.” (National Crime Research Center)

- The most common form of recruitment involves making false promises. Victims are promised good jobs, educational opportunities, promising relationships, and other benefits.

- Exploitation in Nairobi:

RESPONDING TO EXPLOITATION:

How to identify victims?

- Indicators for Adults:

- Believe that they must work against his/her will?

- Unable to freely leave his/her work environment?

- Unfamiliar with the local language/culture where he/she is working?

- Showing signs that his/her movements are being controlled?

- Feeling that they cannot leave?

- Showing fear and anxiety?

- Subjected to violence or threats of violence against themselves or against family members and loved ones?

- Suffering from injuries that appear to be a result of assault?

- Suffering from injuries or impairments from the application of control measures?

- Distrustful of the authorities?

- Threatened of being handed over to the authorities?

- Afraid of revealing their migration status?

- Not in possession of their travel/identity documents?

- In possession of false identity or travel documents?

- Found in or connected to a type of location likely to be used for exploiting people?

- Not aware of his/her home or work address?

- Allowing others to speak for them even when being addressed directly?

- Acting as if under the instruction of somebody else?

- Being forced to work under certain conditions?

- Disciplined through punishment?

- Unable to negotiate working conditions?

- Receiving little or no payment?

- Having no access to his/her earnings?

- Not having any off days?

- Working excessively long hours over long periods without compensation and time off?

- Forced to live in crowded or substandard accommodation to accomplish tasks for the employer?

- Tried to escape from a situation of work or family and been returned?

- Accepted or is about to accept an unclear job offer away from home?

- Had the costs for transport to the destination paid for by facilitators, whom he/she must pay back by working or providing services?

- Social interaction limited to their immediate environment?

- Sick and has had no access to medical attention for a prolonged period of time?

- Acting as if someone else instructed him/her?

- Under the control of an individual?

- Under the perception that he/she is bonded by debt or cultural bondage (e.g. witchcraft bond)?

- Indicators for children:

- Has no or limited access to his/her parents or guardians.

- Travels unaccompanied.

- Travels in groups with persons who are not relatives.

- Travels accompanied by suspicious individuals.

- Is unable to speak/understand the local language.

- Has no friends of his/her own age, except in his/her work area.

- Is engaged in work that is not suitable for children.

- Performs work of a certain nature (e.g. begging on the streets).

- Has no access to education.

- Has no time for play.

- Lives apart from other children in an unhealthy environment, with substandard accommodation inappropriate to the local setting

- He looks intimidated and behaves in a way that is not typical of children his/her age.

- Eats apart from other members of the “family”.

- Is given only leftovers to eat.

- Has scars or injuries on his/her body suggestive of abuse.

- Is suspected to be in a child marriage or involved in child prostitution.

- These indicators are not exhaustive and should be adapted to the context.

How to respond to victims?

- The Kenyan Government has instituted a mechanism by which you can refer cases of suspected human trafficking to first responders, including police, immigration officers, local authorities or non-governmental entities.

- Victims of trafficking often need mental health and other health care services. They may be in distress, so one should be sensitive not to put them in additional danger with their traffickers when extending help.

PREVENTING RECRUITMENT:

- Raise awareness about the methods of human trafficking – especially warn children.

- Parents, be aware that children may be victims of trafficking if not seen for long spans of time.

- If an offer is too good to be true, it likely is – be skeptical of promises.

- If travelling for work/education, take the following precautionary measures:

- Do your research: Gather as much information as possible about where you will be prepared for the trip. Learn about culture, language, and places to seek help if you get into trouble. You should always be aware of the location of the Kenyan embassy or consulate and their contacts.

- Assess the reason for travelling or the offer on the table: One should look at the offer on the table and analyse whether it is genuine or not. Take note of the risks involved. If you are going for education, do you have an official invitation letter from the school? Have you gotten in touch with the school to confirm the validity of the offer? How will you pay for school fees or sustain yourself while in school? If someone has offered help in any way, you should always know the payment terms.

- Identity and Travel Documents: Think about your identity and travel documents.

- What are the required identity and travel documents that you need, and do you have them?

- Please note that you need specific visas to work or study in another country, and you should ensure you have them before you travel. You should not allow anybody to process your identity and travel documents because it will be difficult to know whether they are authentic. Most countries and embassies do not allow people to apply for identity and travel documents on behalf of other people.

- Prior to leaving, do the following:

- Leave behind a copy of all your identity and travel documents and a recent photo.

- Give the address and contact information of where you will be going to your family and friends.

- Get contacts of organizations or people you can contact if you get into trouble. If you are travelling for work, make sure you have a contract and read it to understand what it says.

- Register your contract with the local Labour Office

- Upon arrival, do the following:

- Please inform your family that you have arrived safely and provide them with your latest address and contact information at all times.

- Register with the Kenyan embassy or consulate as soon as you arrive.

- Stay in touch with a community of migrants who are in the same country (e.g., via social media).

How to intervene when someone is at immediate risk of trafficking?

- What to do if someone you know is planning to recruit someone else into a situation of human trafficking (e.g. sell a baby)?

- Direct them to the resources of the Shalom Empowerment Center (SEC) Addressing Violence Against Women and Children in Riruta.

- could be directed to counselling and budgeting help

- The center is available to facilitate and provide advice on referrals.

- Encourage reporting through relevant government institutions, NGOs and proper reporting mechanisms

- What to do if someone you know is planning to take a job abroad that sounds dangerous?

SOME SHALOM-SCCRR CASE STUDIES:

Case 1: Trafficking of babies (adapted from experiences described by women participants in Women & Conflict Workshops at the Shalom Empowerment Center):

Jane, a 21-year-old single mother of three, resides in a cramped home within Kibera. Struggling to make ends meet. She faces extreme poverty, unemployment, and limited access to social support systems.

Jane’s financial situation becomes increasingly dire, making it challenging for her to provide her children with basic necessities. Jane’s youngest child, a newborn baby, has put additional financial strain on the already struggling family. She encounters a woman who recognizes her desperation. The woman offers her a significant sum of money in exchange for her baby, enticing her with the promise of financial relief and promising that she would provide a better life for the child.

Overwhelmed by her financial burdens and lured by the woman’s false promises, Jane contemplates selling her baby as a means to escape her dire circumstances and ensure that she can properly care for her two older children. The traffickers capitalize on her desperation, manipulating her emotions and exploiting her vulnerability for their own gain.

Fortunately, Jane’s situation comes to the attention of a friend in the community who is aware of the dangers of human trafficking. Jane’s friend directs her community-based organization, which is actively working to support vulnerable individuals in the slums. Their team and local social workers intervene to provide immediate assistance and support.

The organization recognizes the presence of traffickers operating in the slums and their exploitative tactics targeting desperate young women like Jane. They assist her in understanding the gravity of the situation and the dangers associated with selling her child. The organization assures her that they are there to support her in finding alternative solutions without resorting to such drastic measures.

Case 2: Job offer abroad (adapted from experiences described by women participants in Women & Conflict Workshops at the Shalom Empowerment Center):

19-year-old Amina dreams of pursuing an education and securing a better future for herself and her family. She sees a job advertisement on social media promising exciting employment opportunities abroad. The recruitment agency assures her of well-paying jobs, free accommodation, the opportunity to travel, and a chance to send money back home to support her family.

The agency’s social media presence seems legitimate, and Amina’s friend also follows them. She figures they must be trustworthy. Unbeknownst to Amina, the recruitment agency is a front for a human trafficking operation. They exploit the vulnerabilities of individuals seeking better opportunities. Their promises convince Amina to sign a contract. She is asked to turn over her passport and birth certificate to the agents. They process a visa for her to go to Saudi Arabia.

Once her visa arrives, Amina is given a plane ticket and her passport. Amina’s journey begins with a flight to a neighbouring country, where she is handed over to someone from the recruitment agency whom she does not recognize. This agent confiscates her passport and explains that it will be returned upon arrival in Saudi Arabia, her destination. Amina is transported across borders through irregular means, evading official checkpoints.

Upon reaching Saudi Arabia, Amina’s passport is not returned, and she is confined to a cramped and overcrowded living space with several other trafficking victims. Amina’s personal belongings are confiscated, and she is subjected to physical and psychological abuse by the traffickers.

Amina is taken to another town alone and introduced to a family. She is told they would be her employers. Amina’s dreams of a decent job quickly shatter as she is forced into domestic servitude. She is made to work excessively long hours with minimal rest or adequate food. Her movements are restricted, and she is under constant surveillance. The conditions are deplorable. She is subjected to physical and verbal abuse by her employers. She is not paid for her work, as her employers tell her she must still pay off her travel expenses.

The constant vigilance of her employers makes it nearly impossible to escape. Even if she could escape, she was never given her passport back and was not paid any wages. It would be impossible for her to return home to Kenya.

Fortunately, Amina’s plight comes to the attention of local police and an anti-trafficking organization operating in the area. They conduct a rescue operation in coordination with law enforcement agencies, raiding the location where Amina and other victims are held captive. Amina is freed from her captors and provided with immediate medical attention and shelter.

Case 3: Organ trafficking scheme (adapted from experiences described by women participants in Women & Conflict Workshops at the Shalom Empowerment Center):

At a bustling bus station in Nairobi, a young woman named Sarah is waiting for her matatu to return home after a tiring day at work. As Sarah waits, a stranger seems to faint next to her, causing a commotion among concerned onlookers. A stranger nearby runs to help the fainted man. The stranger asks Sarah to help him get the collapsed man into his car to take him to the hospital.

In a moment of compassion, Sarah agrees to accompany the man to a nearby vehicle under the pretence of taking the unconscious man to the hospital. She helps carry the man to the car and gets inside. Once inside the car, the man offers Sarah a drink of water. Unbeknownst to her, the drink is laced with drugs, rendering her unconscious and defenceless.

Sarah awakens in a dark, unfamiliar, small room. She feels woozy from the drugs she was given. She hears men talking in another room. They say that they have tested her organs but that they are not in good enough condition to sell. Their intention was to kidnap Sarah, forcibly remove her organs, and sell them. Prior to removing her organs, they performed medical tests on her, which found that her organs were in poor condition and could not be sold, so they should instead just kill Sarah.

As they were speaking, they assumed Sarah was still unconscious from the drugs. Because she was awake, Sarah heard their plans and could escape through a window.

Authors:

Rev. Dr. Patrick. R. Devine, Shalom-SCCRR International Chairman

Ms. Paula Soumaya Domit, MA, Harvard Kennedy School, Masters of Public Policy Program (Shalom-SCCRR International Volunteer Consultant)

APPENDIX:

SOURCES:

International Organization for Migration, Assessment Report on the Human Trafficking Situation in the Coastal Region of Kenya, 2018, https://kenya.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl926/files/documents/ASSESSMENT%20REPORT%20ON%20HUMAN%20TRAFFICKING%20SITUATION%20%20-%20COASTAL%20REGION%20KENYA%20REVISED%20LOWRES%2023072018%20F_0.pdf

National Crime Research Center, Human Trafficking in Kenya – 4th Draft Report, 2015, https://crimeresearch.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Human-Trafficking-in-Kenya.pdf

Ministry of East African Community (EAC), Labour and Social Protection, Guidelines for a National Referral Mechanism for assisting victims of human trafficking in Kenya, N.D., https://www.socialprotection.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/NRM-Guidelines-for-Kenya-law-res.pdf

Chrisostim Wanyonyi Munialo, Factors that Facilitate Human Trafficking: A Case Study of Nairobi City, 2010, http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/11295/105506/Munialo%20_Factors%20That%20Facilitate%20Human%20Trafficking%20Into%20Kenya%20A%20Case%20Study%20Of%20Nairobi%20City.pdf?sequence=1

UNODC, Report on the Urban Safety Governance Assessment in Mathare, Nairobi City, 2021, https://www.unodc.org/pdf/criminal_justice/UrbanSafety/Report/USGA_UNODCity_Nairobi_Final_Report.pdf

UNOCDC, https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/Toolkit-files/08-58296_tool_1-1.pdf

USA Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report, June 2008. U.S. Department of State Publications 11407. https://2001-2009.state.gov/g/tip/rls/tiprpt/2008/

Dorfman, A.,’ Speak Truth to Power; Voices from Beyond the Dark’, based on the book by Kerry Kennedy – Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights, (2010) p. 2.

Moran. M. (2022). Shalom Empowerment Center (SEC) opens in Nairobi, Kenya. https://www.indcatholicnews.com/news/45158

Shalom-SCCRR. (2024). Who We Are 2023-2024.

https://shalomconflictcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Shalom-SCCRR-Who-We-Are-2023-2024.pdf

Shalom-SCCRR. (2024). 2023 Shalom-SCCRR Results and Achievements.

Shalom-SCCRR. (2024). 2009-2023-Shalom-SCCRR-Results-and-Achievements.

Noonan, O., Okoth G., & Kibe, E. (2024). The Intergovernmental Agency for Development (IGAD) and Shalom Center for Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation (SCCRR): MoUs Operationalized in Peace and Development. https://shalomconflictcenter.org/the-intergovernmental-agency-for-development-igad-and-shalom-center-for-conflict-resolution-and-reconciliation-sccrr-mous-operationalized-in-peace-and-development/

Otsieno, J. (2024). Nairobi Slums’ Structures for Conflict Transformation: Shalom-SCCRR Trained Negotiation and Community Facilitators (CFs) Continue to Initiate Village/Ward Level Forums for their Leaders to Negotiate Communal Conflicts. https://shalomconflictcenter.org/nairobi-slums-structures-for-conflict-transformation-shalom-sccrr-trained-negotiation-and-community-facilitators-cfs-continue-to-initiate-village-ward-level-forums-for-their-leaders-to-negotiate-commu/

Devine, P. R. (2017). “Radicalization and Extremism in Eastern Africa; Dynamics and Drivers”, published in the Journal of Mediation and Applied Conflict Analysis, 4 (2): http://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/9086/7/PD-Radicalisation-2017.pdf

Lugonzo, F. (2018). Conflict transformation, Radicalization and Extremism in Eastern Africa. https://shalomconflictcenter.org/conflict-transformation-radicalization-and-extremism-in-eastern-africa/

https://shalomconflictcenter.org/

https://maryandjosephlifecenter.org/

Video on the Launching of the Shalom-SCCRR Human and Organ Trafficking Module: https://youtu.be/5e9tCDeh1fY